When you drive along Avenue Abderrahim Bouabid, the road connecting the Hay Riad and Agdal neighborhoods to Rabat, it’s hard to miss them. In the heart of a 13-hectare site, the constant movement of these red cranes dominates the landscape.

The construction site is impressive, even disorienting, in terms of height for a city accustomed to buildings up to four stories. This impression is heightened by the cranes working on the neighboring site of the new Cheikh Zayed Foundation Hospital.

Launched by King Mohammed VI in May 2022, the construction of the new Ibn Sina University Hospital will provide the capital with a modern hospital, including a 33-story hospitalization tower, a medical-technical center, and another eleven-story tower dedicated to cardiovascular disease treatment. Six billion dirhams have been allocated to this colossal project, which is scheduled for completion in 2026.

A little further along, the current Ibn Sina University Hospital continues to operate. The staff working there daily are uncertain about their future, as no transfer policy has been initiated by the hospital’s management. As usual, the hospital is plagued by numerous problems affecting its operation: governance, lack of equipment, and human resources…

Especially since the future of human resources is currently uncertain. The empty neighboring medical faculty contrasts with the bustling construction site. The premises are deserted by students who have been on strike for over six months to protest the government’s decision to reduce the duration of medical training (from 7 to 6 years).

The Executive refuses to concede on this demand but has made numerous overtures to the students, who cling to their main demands. One might almost wonder if these medical students will ever be able to occupy and work in the new, state-of-the-art CHU being built just steps away from their faculty…

“Abdelaziz Adnane, the head of CNOPS, sees an imminent danger on the horizon: the financial imbalance of the AMO poses a real risk of system bankruptcy.”

A few kilometers away, in the heart of the capital, Abdelaziz Adnane, the head of CNOPS, faces a more pressing issue. While the question of human resources in the healthcare sector is undeniably significant, Adnane is even more concerned about the sustainability of the Moroccan healthcare system in the medium and long term.

CNOPS is a key player in the expansion of the mandatory health insurance (AMO) mandated by the king. However, its general director foresees an imminent threat: the financial imbalance of the AMO poses a real risk of the system collapsing. If nothing is done quickly, the AMO could be heading straight for disaster, according to several experts we consulted. As is often the case, the issue stems from a lack of clear coordination and governance.

Royal Will

The origin of Morocco’s Mandatory Health Insurance (AMO) stems from a royal decree. During a speech delivered amidst the COVID-19 crisis, King Mohammed VI declared that « the time has come to launch, over the next five years, the process of generalizing social coverage for all Moroccans. » This ambitious project is one of four pillars in the broader social coverage reform.

To fund this program, the state is banking on increased tax revenues and a broader tax base, as indicated by Budget Minister Fouzi Lekjaâ during a recent parliamentary session.

The project also enjoys a legislative boost. In 2021, the Prime Minister adopted 28 decrees to extend eligibility for the AMO to three million self-employed workers (a category that includes professionals, freelancers, and traders), as well as their dependents (essentially their families).

At the end of 2022, Parliament adopted a law proposed by the Ministry of Health that extends the Mandatory Health Insurance (AMO) to four million beneficiaries of the RAMED (Medical Assistance Regime for Disadvantaged Populations introduced in the 2000s) and their six million dependents.

The state budget will cover their contributions. These developments allow the Akhannouch government to claim that « an additional 22 million people now benefit from Mandatory Health Insurance, » a statement reiterated multiple times before both Parliament and the Government Council.

An expansion campaign that brings the number of Moroccans eligible for AMO to 29.8 million. The social machinery is now in motion. Its positive impact on millions of Moroccans is undeniable. However, without government action, this well-oiled machine could become jammed or even break down, risking leaving millions of citizens stranded.

Uncontrolled Expenses

The problem? AMO expenses are significantly higher than its revenues, and the trend is worsening. “We launched an ambitious project, but no one seems to have a precise idea of what it will cost. Without a comprehensive actuarial study, the government seems to be operating blind,” says a source in the sector. This study should account for the expenses and revenues of all schemes, as well as the evolution of the nature and costs of AMO expenses.

However, today, each organization manages its scope in isolation. The ANAM, which is supposed to coordinate health insurance, has been largely ineffective in this area. Its actions, and especially its inaction, have significantly contributed to worsening the situation for managing organizations, as evidenced by the national agreements that ANAM tried to impose on CNOPS and CNSS in 2020.

Had these agreements been applied, the managing organizations would be in financial ruin, and the generalization of health insurance would no longer be feasible. The upcoming replacement of ANAM by the High Authority for Health, promoted to the status of a strategic institution during the last Council of Ministers chaired by the King, could be an opportunity to ensure real regulation of the system. In the meantime, expenses continue to rise: medications, tests, medical devices, radiology… the tally cotinues to rise.

Medications are too expensive

Medication prices can be reduced by 30 to 50% through a simple government decision. “Up to 80% for expensive medications,” an expert tells us.

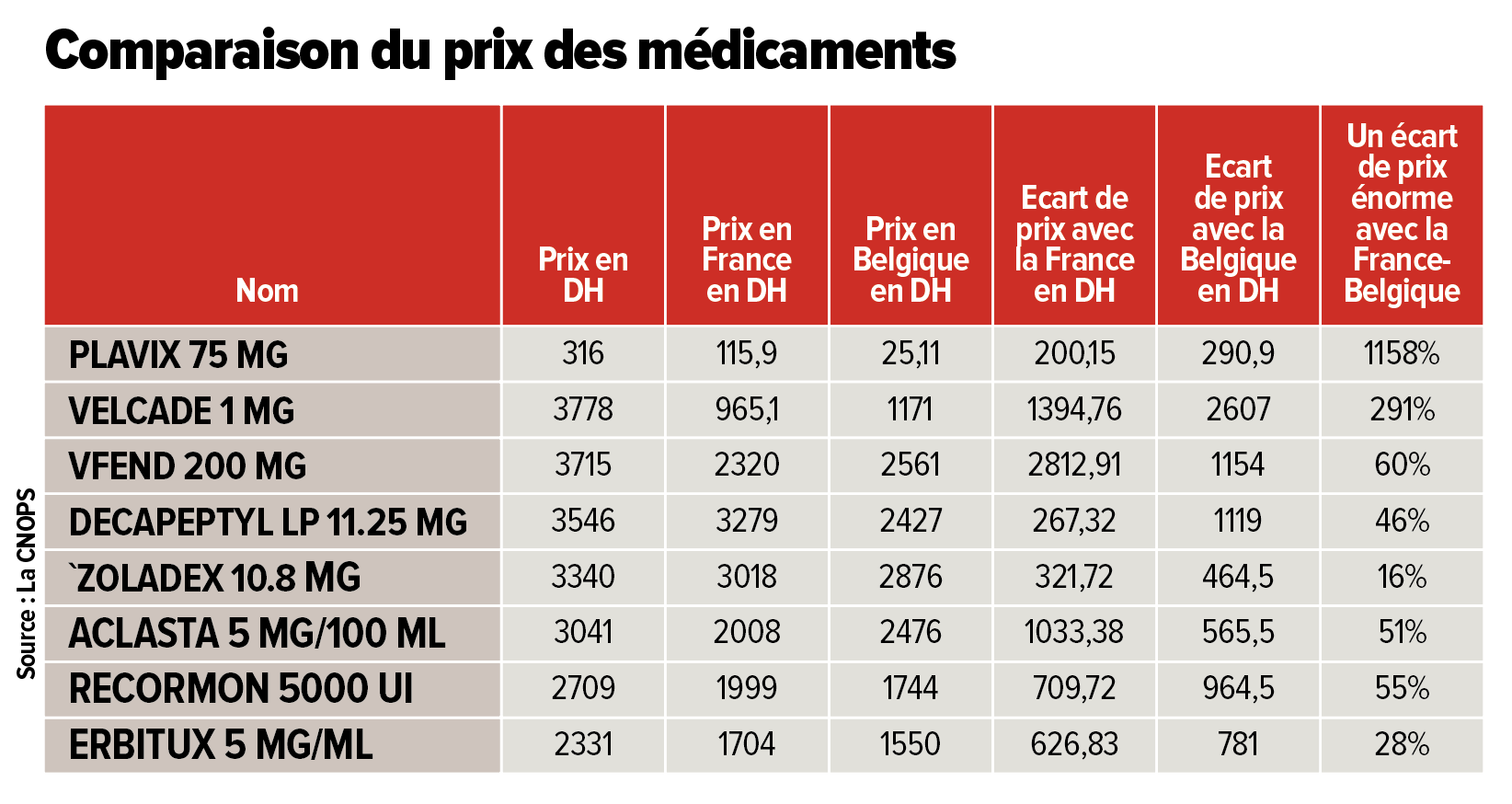

The case of medication prices is emblematic of the lack of governance affecting the AMO. For over twenty years, reports, studies, and benchmarks have consistently reached the same conclusion: medications in Morocco are expensive, very expensive. Their prices could drop by 30 to 50% through a simple government decision. « Up to 80% for expensive medications, » says an expert who has studied drug prices worldwide.

Yet, nothing seems to persuade the government to take action. « Even though they account for only 25 to 30% of AMO expenses, a significant reduction in their prices could save several billion dirhams for the AMO. » Nevertheless, various successive governments have distinguished themselves by their inaction in this area.

The influence of certain pharmaceutical importers and manufacturers’ lobbies blocks any action from the managing bodies. Thus, the number of medications covered by the AMO has more than quadrupled in 18 years, rising from 1,001 to 4,825. The number of covered medical devices has increased more than fivefold, from 168 to 883.

Even worse, this expansion occurred in the « lamentable absence of medico-economic studies and impact assessments, » according to a CNOPS document consulted by TelQuel. In short, neither the prices of these medications nor their clear impact on patient health were assessed before their inclusion in the care basket, sometimes with astonishing consequences.

« If the prices of the 321 drugs applied in France or Belgium had been applied in Morocco, CNOPS would have saved 600 million dirhams per year, » the CNOPS document reads. For instance, Plavix, a medication prescribed for myocardial infarction, costs 316 dirhams in Morocco, while the same medication is sold for 25 dirhams in Belgium.

Another medication, Velcade (a powder injection for treating bone marrow cancer), costs 3,778 dirhams in Morocco, whereas it is priced at 965 dirhams in France.

There are hundreds of such examples, and the impact of reducing their prices would amount to billions of dirhams. Controlling healthcare expenses is one of the tasks assigned by law to ANAM, but it does not seem to be a priority for its officials. Solutions do exist and have been outlined in several studies and reports by the Court of Auditors, the parliament, and the CESE.

Public vs private

Another source of deficit is the healthcare services provided by the private sector. “The sacred principle of AMO is to offer the same insurance to everyone,” says Hassan Boubrik, Director General of the CNSS. In practice, applying this principle means that eventually, all Moroccans, regardless of their contribution amounts, will be reimbursed by AMO for care provided in both public and private healthcare facilities.

This situation directly pits the two offers against each other, as noted by this sector player: “AMO has led to a paradigm shift. Now, even in public facilities, patients are regarded as clients. This poses a major challenge for the Ministry of Health: it must upgrade its healthcare structures while being able to compete with a rapidly expanding private sector.”

On the ground, the public sector suffers from an uneven distribution of healthcare services across the country. This issue is expected to be addressed by the future establishment of GSTs (Territorial Health Groups), which will be responsible for distributing public healthcare services. “A resident of a small town, who is solvent and covered by AMO, cannot receive care close to home. Medical deserts are numerous, and public healthcare facilities in small towns often lack the human resources and equipment needed to provide quality care,” warns our source.

If this hypothetical AMO beneficiary travels to the Casablanca-Kénitra axis for treatment, they would likely choose a private facility, which is more available and better equipped compared to often overwhelmed and under-resourced public hospitals.

“The development of private clinics would have been a boon for the state if the private healthcare offer were located where the public sector falls short. However, private clinics, currently concentrated along the Casablanca-Kénitra axis, encroach upon the public sector, depriving it of both human resources and potential clients,” observes our expert.

A public offering that falls short

However, the existence of a strong public sector is a prerequisite for the success of the AMO. The principle is simple: the AMO reimburses both private and public healthcare services. Public healthcare is less costly, meaning that using public health facilities is less expensive for the AMO and, consequently, for the state budget, which covers a portion of the AMO contributions.

To promote this virtuous cycle, the CNSS (responsible for social coverage for private sector employees) and the CNOPS (responsible for social coverage for public sector employees) have launched various initiatives. One such initiative effectively exempts all beneficiaries of AMO Tadamon (which covers the most vulnerable categories) from medical costs if they choose to be treated in public facilities, with the state handling the payment.

Conversely, if beneficiaries of AMO Tadamon choose a private facility, they will need to pay a co-payment for the portion of the costs not covered by the insurance scheme. Another initiative allows public hospitals to bill the CNSS directly for patients covered by the CNOPS, eliminating the need for prior authorization from the insured.

However, some sector observers argue that the state’s insurance policy has not been sufficiently thought out to ensure its success. For example, “AMO Tadamon is a mistake in the sense that it is this product that should have been universalized for all citizens, as it provides free access to public hospitals. One could have imagined universal coverage for everyone, providing an average basket of care of 1500 dirhams per year per person, which could ensure the financial balance of the scheme. Those who can afford to pay will contribute their premiums, and the less fortunate will be compensated by the state. This situation would allow different schemes, such as the CNOPS or the CNSS, to offer complementary insurance while involving a private sector that feels currently sidelined,” notes this sector expert.

In summary, through the AMO offer, public hospitals could have attracted more patients away from private ones. This view is shared by the director of the CNOPS, who advocates for a gradual universalization.

The director believes that this process must be preceded by an actuarial study to assess the cost of this standardization, also considering the impact of revising the National Reference Pricing (public price of a service or drug) to “align financial engineering with any decision that has a financial impact on the AMO managing funds.” But for now, 90% of AMO financial resources allocated for reimbursing care are being captured by private clinics.

A multitude of abuses

In 2006, Morocco had 248 private clinics. Eighteen years later, this number has nearly doubled, with the country now having 446. Some of these clinics are part of structured groups such as Akdital (listed on the Casablanca Stock Exchange), CIM Santé, or Oncologie et Diagnostic du Maroc (ODM), among others.

Some of these facilities address a real need among citizens by compensating for the shortcomings of the public sector. In recent years, some of them have distinguished themselves through significant improvements in their healthcare services, technical and human resources, and governance.

As the dominant player in the market, the private sector still shows numerous shortcomings. One major issue is the lack of transparency. For example, there is no comprehensive health reference framework ensuring access to all essential information about a private clinic. « Private sector players only provide the clinic’s business name and the name of the medical director. No visibility is given on the technical facilities they manage. Do they have an MRI machine? Are they authorized to perform resuscitation? » questions Abdelaziz Adnane, Director General of CNOPS.

The public official has repeatedly submitted requests to the National Health Insurance Agency (ANAM, which currently regulates the health insurance sector pending the establishment of the future High Health Authority) to clarify matters. However, he has been met with complete silence, never receiving any responses.

In addition to this lack of transparency, there are also “unorthodox and, more importantly, illegal practices,” reported by both CNSS and CNOPS officials. “We identify private facilities where expenses have skyrocketed or increased significantly, and we systematically launch control missions to understand the situation,” Hassan Boubrik assures us.

For its part, CNOPS has developed a platform called CNOPS 360°, which allows it to detect any atypical or abusive behavior by its members or their doctors. Through this tool, the organization has been able to identify practices such as double billing for procedures or even billing for fictitious services. The software also helps detect the overconsumption of certain costly medical procedures.

For instance, CNOPS discovered private clinics where doctors consistently used active stents (a medical device used to treat arterial narrowing or blockages) on patients who did not need them. In Morocco, the reimbursement rate for this device can reach 12,500 dirhams, whereas in France, the same procedure is reimbursed at 510 euros, or 5,553 dirhams.

At CNOPS, it is believed that there must be a firm establishment of « the prohibition of security deposits, overcharging, refusal of coverage, and selective billing by private clinics. »

But beyond mere fraud control, it is also necessary to enhance financial protection for insured individuals during hospitalization. At CNOPS, it is believed that there must be a firm establishment of « the prohibition of security deposits, overcharging, refusal of coverage, and selective billing. »

To limit these abuses, a national commission to combat health insurance fraud could be created, involving, in addition to the AMO management organizations, the General Directorate of National Security (DGSN), the General Directorate of Taxes (DGI), and the Customs and Indirect Taxes Administration (ADII).

This commission would be responsible for « coordinating technology, systems, and fraud monitoring, profiling suspicious behaviors and strengthening the alert and combat system, and finally, initiating coordinated actions in legal matters, » explains Abdelaziz Adnane.

Lobbying by the private sector

This is the reality the CNSS and CNOPS must navigate: a weak public healthcare offering coupled with an increasingly effective yet costly private sector. Adding to this is the lobbying by private sector players to push for an increase in the National Pricing Tariff (TNR, Tarif national de référence), which sets the cost for medical services. This could impose additional burdens on the AMO through higher service prices.

« I am not opposed to revising the TNR, as our main goal is to minimize out-of-pocket costs for our insured. However, we must consider the financial balance of the schemes, and especially, contemplate revising the TNR in both directions, as several services deserve a downward adjustment, » says Hassan Boubrik, Director General of the CNSS.

« The surpluses generated by the CNSS, with all populations integrated into the scheme, are at risk of dissipating, as was recently the case with the CNOPS, » warns an expert

The fund currently enjoys a certain financial comfort with a surplus of 40 billion dirhams. However, these reserves are at risk of vanishing quickly. « The surpluses generated by the CNSS, with all populations integrated into the scheme, could evaporate, as was recently the case with the CNOPS, » warns an expert.

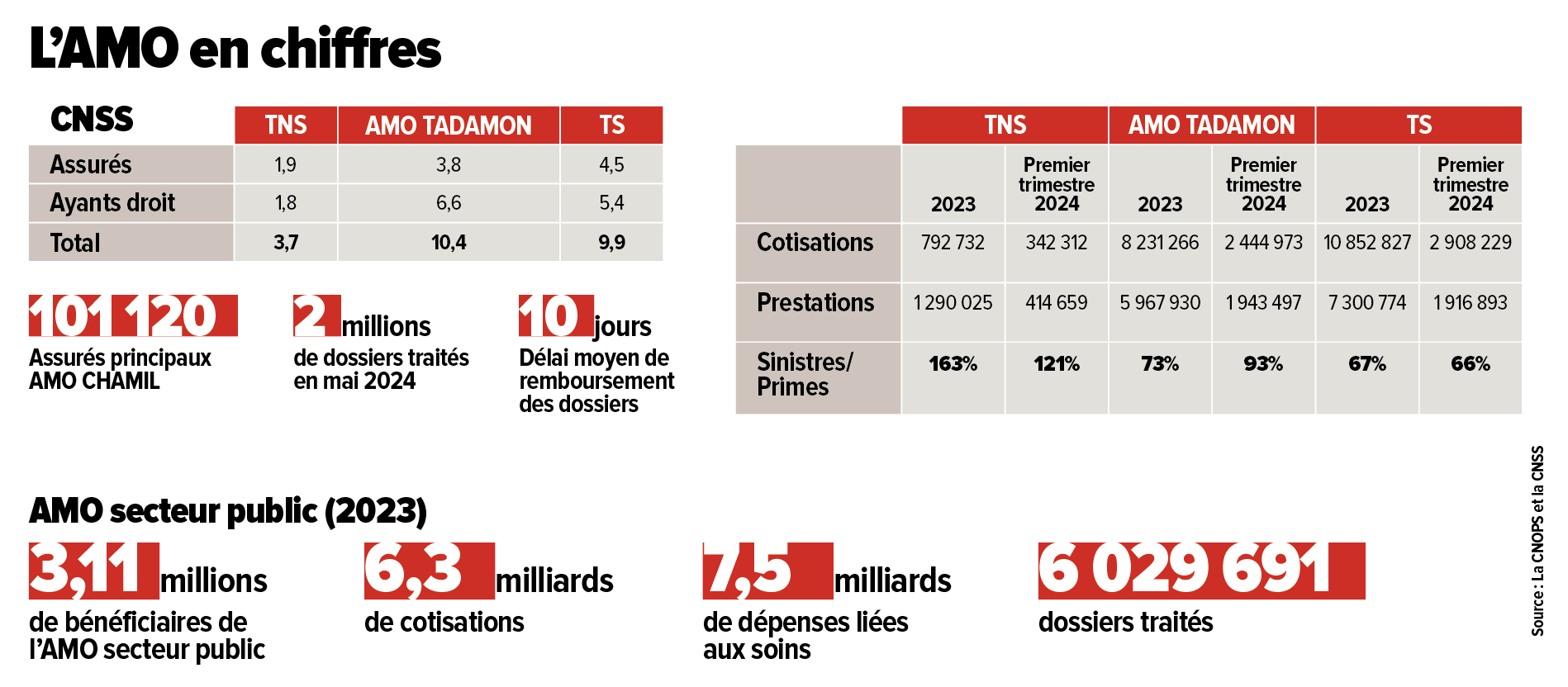

According to the latest figures, the CNSS is already experiencing significant imbalances. In 2023, for non-salaried workers, 793 million dirhams were collected in contributions, while the amount spent by the CNSS on medical benefits reached 1.3 billion dirhams. And this phenomenon could worsen with the continued expansion of AMO coverage.

The CNOPS, on the other hand, has been in the red for three years. The scheme has been experiencing consecutive deficits: 1.5 billion dirhams in 2021, 878 million in 2022, 1 billion in 2023, and 1.34 billion projected for 2024.

The CNOPS, on the other hand, has been in the red for three years, with consecutive deficits: 1.5 billion dirhams in 2021, 878 million in 2022, 1 billion in 2023, and 1.34 billion projected for 2024. « These deficits have affected payment delays to healthcare providers and reimbursements to insured individuals, even though the CNOPS drew 1.6 billion dirhams from its reserves in 2023 to continue meeting its obligations, » explains Abdelaziz Adnane.

So far, the CNOPS’s critical financial situation has not prompted any reaction or intervention from the ANAM or the Executive. Yet, the solutions are identified and concern both revenue and expenditure. They have been approved by the organization’s board of directors and are awaiting a government decision for implementation.

AMO is at a Crossroads

Just like the AMO reform, the new Ibn Sina University Hospital could turn into a financial black hole for the state in the coming years.

Despite the looming danger, calm prevails in the capital. When walking down Abderrahim Bouabid Avenue, one might think that the new Ibn Sina University Hospital is the perfect metaphor for the AMO project. Expensive, it represents one of the flagship elements of the health reform initiative. It could even ensure its success. However, this hospital, just like the AMO reform, could turn into a financial sinkhole for the state in the coming years.

The AMO is currently at a critical phase in its development. Without urgent government intervention, this essential component of universal social protection, supported and championed by the king, risks heading straight for disaster. Governance, regulation, and control—everything needs to be reassessed to ensure the project’s long-term sustainability and to provide Moroccans with the care they deserve.

The impasse of the self-employed

Integrating self-employed workers (TNS), including professionals in the liberal sector and independent workers, into the AMO framework is crucial for the success of this major social undertaking.

According to Hassan Boubrik, General Director of CNSS, 3.7 million self-employed workers (TNS) are now registered with the AMO, including 1.9 million insured individuals. This is still far from the target announced by Fouzi Lekjaâ to cover 7 million TNS, including 2.3 million insured and 4.7 million dependents. Nevertheless, according to Boubrik, considerable efforts have been made to extend coverage to this group in collaboration with various stakeholders.

« The registration process for TNS starts with liaison organizations, such as the Ministry of Agriculture for farmers, the Order of Architects for architects, and the Ministry of Health for healthcare providers, » he explains.

« We have implemented digital tools allowing TNS to register through the CNSS portal, where they can obtain their login credentials and register their family members, » adds Boubrik.

A major issue with this category is unpaid contributions. According to Saâd Taoujni, an insurance expert, only 17% of TNS were up-to-date with their AMO contributions as of the end of February 2024, leaving nearly 9 million TNS without insurance.

« The government ultimately recognized the difficulty of covering this group by writing off a debt of 3.4 billion dirhams through the passage of a law granting them amnesty, » explains Taoujni. For Hassan Boubrik, the main challenge in generalizing AMO for TNS is indeed the regularization of this population. The CNSS aims to regularize 50% of the TNS population using « all legal means, including forced collection. »

Having a single managing fund for the AMO

The transfer of the management of the public sector AMO scheme from the CNOPS to the CNSS is about to be realized.

In December 2023, the Ministry of Economy and Finance, which oversees the AMO managing funds, submitted a draft law regarding this transfer to the General Secretariat of the Government. It is now awaiting review by the government council to proceed through the legislative process.

In the meantime, Fouzi Lekjaâ’s teams are developing various scenarios for this merger without disclosing any information to the public or even to stakeholders involved in the project. “The CNOPS was not involved in this project, which was initiated without a national strategy for expanding, sustaining, and reforming AMO governance,” confirms Abdelaziz Adnane, director general of the CNOPS.

He notes that the project raises several concerns, particularly regarding the fate of CNOPS employees and the protection of their rights. This includes 879 CNOPS employees and 1,009 liquidators working for the eight mutual funds affiliated with the organization.

“The CNSS has outsourced the processing of medical claims to Intelcia and also relies on local points of contact, whereas the CNOPS and the mutual funds manage this through their own staff. What will happen to these individuals?” questions the CNOPS director general.

Furthermore, he emphasizes the need for a comprehensive impact assessment, both in the short and long term, “not only on the financial sustainability of the scheme but also on organizational aspects, relationships with mutual funds, integration with complementary coverage, financing parameters, and the mechanisms for controlling medical expenses.”

CNOPS 360°, an essential tool in the fight against fraud

With eyes shining with enthusiasm, Abdelaziz Adnane, Director General of CNOPS, introduced us to the CNOPS 360° platform, which was designed nearly 3 years ago to combat fraud. “This risk management and medical control system has enabled us to detect and prevent numerous irregularities in basic medical coverage,” he explains.

In 2023, CNOPS conducted rigorous checks using this platform to verify the eligibility of new registrants. Out of 1,665 registration requests for male spouses, 45% were rejected after cross-referencing with the DGSN database. For female spouses, 7% of the 18,738 requests were denied. In total, 10% of registration requests were rejected, explains the director of this organization that manages the public sector AMO.

Moreover, this new platform has enabled CNOPS to implement several control actions to ensure the accuracy of services. “This platform allows us to have a real-time overview of medication consumption, biological analyses, radiological tests, and various health services for any insured individual. It also enables us to monitor the behavior of service providers and detect significant increases in expenses at private care facilities, which are then subjected to audits by our teams and sometimes external auditors,” says Abdelaziz Adnane.

For example, the circularization of insured individuals helped identify 20 cases of non-receipt of services among 108 returned letters, leading to the suspension of a service provider. A review of cesarean sections over a four-year period uncovered a case of elective cesarean. Additionally, 113 cases were examined to detect double billing, particularly in areas such as intensive care and dialysis.

A check on a sample of files on this platform also verified the compliance of prescriptions for expensive medications. Among the interception examples, a physical inspection at a hemodialysis center revealed discrepancies between the number of billed dialysis sessions and those actually performed, as well as between the prescribed and administered erythropoietin vials.

In Settat, a clinic billed for days of intensive care while the patient was actually receiving home oxygen therapy.

In Settat, a clinic billed for days of intensive care while the patient was actually receiving home oxygen therapy. Two insured individuals were identified for excessive use of MRIs, with no record of the exams in the radiology center archives.

Since the start of its anti-fraud mission with this platform, CNOPS has filed 34 complaints, including 16 in 2023, involving 160 insured individuals and 7 healthcare providers. “Despite the considerable efforts made by CNOPS to combat fraud, weaknesses remain, particularly the need to cross-reference files on a national scale and to improve medical control mechanisms,” regrets Abdelaziz Adnane.

To strengthen the fight against fraud, the CNOPS General Director recommends revising the delegated management agreement and creating a National Commission for Social Fraud Prevention, bringing together the main stakeholders involved. The CNOPS 360° platform thus proves to be an essential tool for ensuring rigorous management of health expenditures and promoting universal and equitable medical coverage.

Written in French by Yassine Majdi and Younes Saoury, edited in English by Eric Nielson