It is a window into a painful chapter of Morocco’s history. In a rare display of frankness, Abdellatif Jouahri reflected in detail on a tumultuous episode of the 1980s for the IMF’s website (IMF.org): the Structural Adjustment Program (PAS) period.

In a fascinating interview, Jouahri reveals the intricacies of an event that many Moroccans experienced firsthand, but whose deeper context remains largely unknown

In a fascinating interview conducted by Taline Koranchelian, the IMF’s Deputy Director for the Middle East and Central Asia, in late August 2023, Jouahri reveals the intricacies of an event that many Moroccans experienced firsthand, but whose deeper context remains largely unknown.

The current Governor of Bank Al-Maghrib, the strict guardian of Morocco’s monetary balance for the past 20 years, opens up with surprising confessions. He takes us back to the early 1980s, a time when Morocco’s economic outlook began to darken. Back then, short on foreign currency and budgetary resources, the kingdom had no choice but to submit to the IMF, bound hand and foot.

As the lender of last resort, the International Monetary Fund, born from the Bretton Woods agreements, steps in to rescue exhausted Third World economies, in exchange for harsh reforms and severe cuts to public spending. Morocco, like many other poor nations, was not spared. Technocrat to the core, Abdellatif Jouahri found himself unwillingly at the heart of the storm.

Jouahri had to contend with hardline politicians who refused to tighten their belts despite the dire state of public finances

When he was appointed Minister of Finance in Maâti Bouabid’s government (1979-1983) in 1981, Jouahri found himself face-to-face with political heavyweights like Mhammed Boucetta of the Istiqlal Party, then Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, and Mohamed Douiri, who held the portfolio for Public Works. Prime Minister Maâti Bouabid, a former member of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP), had shifted to the Makhzen’s camp but retained a leftist core, making him suspicious of any austerity policies.

Jouahri thus had to contend with hardline politicians who refused to tighten their belts despite the dire state of public finances. It’s worth noting that the country had just emerged from a period of abundance during which foreign currency reserves reached record highs thanks to an unprecedented rise in phosphate prices.

When the rock falls

« Between 1976 and 1978, the choices were simple. When your resources plummet while you’re on a high spending trend for investment and operations, there aren’t many solutions » says economist Najib Akesbi

As the state coffers filled rapidly thanks to external demand for phosphate, the country embarked on flashy infrastructure investments, instituted subsidies on basic foodstuffs, hired civil servants en masse, and dove headfirst into an openly protectionist policy.

The all-powerful state erected customs barriers to protect local production and managed the economy as much as possible. However, the sudden drop in phosphate prices quickly disrupted the budgetary balance.

« Between 1976 and 1978, the choices were simple. Any person with a minimum of common sense could have made the rational decisions needed. When your resources plummet while you’re on a high spending trend for investment and operations, there aren’t many solutions » says economist Najib Akesbi.

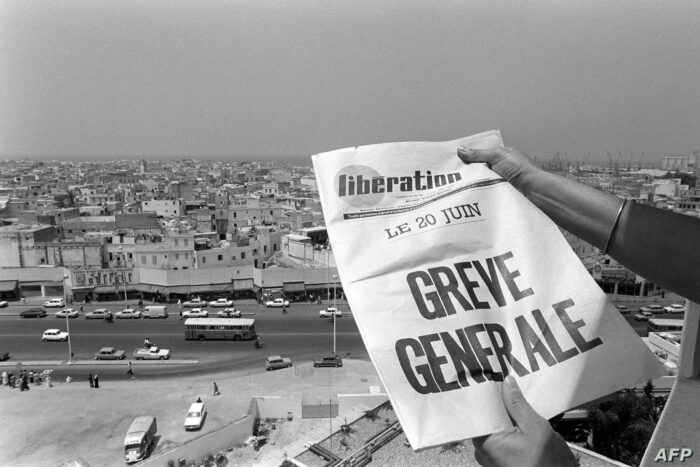

The Bread Riots

Instead of implementing the necessary internal reforms, the state chose to maintain its extravagant lifestyle by resorting to foreign debt, and at exorbitant interest rates no less. When the phosphate boom dried up, the government abruptly decided to cut subsidies on food products.

The price of flour skyrocketed by 50%. The government then faced the infamous 1981 bread riots, which resulted in around 66 deaths according to the Interior Ministry (114 according to the Equity and Reconciliation Commission, and 600 according to unions).

A state of emergency was declared in Casablanca, where tanks from the Royal Armed Forces (FAR) were deployed to control the massive crowds. The unions fiercely opposed the government’s shift to anti-social policies.

With its back against the wall, the state, despite minimal budgetary flexibility, reinstated subsidies to their pre-riot levels, choosing to deepen its debt to preserve social peace and calm the unrest in the streets. It was in this tumultuous context that Jouahri took over his ministerial portfolio.

« We have no more foreign currency! »

At that precise moment, Morocco had just over two days of foreign reserves left. Jouahri was stunned. “What do you mean we have no more currency?” he panicked

At that time, the global economy was grappling with the aftermath of the 1979 oil shock. Interest rates were skyrocketing, and oil prices were hitting record highs. Concerned, Jouahri tried to convince the government’s key figures of the need for potential austerity measures, but he faced strong resistance.

In February 1983, he recalls having a meeting with the vice-governor of the central bank in his office in Rabat, when the director of the department managing the kingdom’s foreign exchange reserves urgently called him.

Panicked, the senior financial official dropped a bombshell: « We have no more foreign currency. » At that precise moment, Morocco had just over two days of foreign reserves left. Jouahri was stunned. “What do you mean we have no more currency?” he panicked. After the initial shock, his first instinct was to immediately inform « His Majesty. »

No more light

Hassan II was staying at his palace in Fez at the time. Upon arriving in the imperial city, Jouahri entered the hotel suite of the king’s chief of protocol, who asked him, “What’s going on?” Jouahri reiterated his request to meet with the monarch immediately.

However, the chief of protocol didn’t grasp the urgency of the situation. To convey the gravity of the problem, Jouahri used a metaphor: “Tomorrow, the light you have in this suite might not turn on anymore.”

The next day, Hassan II received the kingdom’s finance minister. “The king, in a short-sleeved shirt, was sitting in an armchair, in front of a wrought-iron window,” Jouahri recalls in the IMF interview. Hassan II inquired about the situation. “Your Majesty, we have no more foreign currency,” Jouahri said. “So, what do you propose?” the sovereign responded, remaining calm despite the severity of the situation.

“Your Majesty,” continued Jouahri, “this is a completely new situation for me, but give me 48 hours, and I will contact the IMF team.” The kingdom’s finance minister then took a plane to Washington to present the situation to the leaders of the international organization.

A highly tense cabinet meeting

Upon his return to Morocco, Jouahri proposed to Hassan II the formation of a commission to draft a supplementary Finance Law—an extreme solution to adjust the country’s economic trajectory in the face of external shocks. Jouahri suggested cutting defense spending, which he considered to be « budget devouring. »

However, Hassan II, as the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, engaged in a war against the Polisario, did not want to publicly discuss the issue. He suggested that Jouahri retreat to his secondary residence in Fez with his team to devise a plan. Meals were to be covered by the Palace. The goal for these two days was to draft the general framework for the supplementary Finance Law.

The challenge was immense. But who would dare oppose the will of Hassan II? Jouahri took on the task. By the end of the deadline, he emerged from the royal residence with a roadmap in hand. « It was April 30th, » Jouahri recalls. « I returned to His Majesty with the program, and he told me: cabinet meeting that same evening. »

An economic harka

As an introduction to the Cabinet meeting, the king quickly captured the ministers’ attention with a reference to history: “By tradition, when the country was in difficulty, my ancestors from the Alaouite dynasty would mount their horses and launch a harka (a punitive expedition against rebellious tribes). Well, in the current circumstances Morocco is facing, which are very difficult, I too will go to battle; those who wish to follow me are welcome, and to those who refuse, know that I will not hold it against them,” the king declared.

Needless to say, all the ministers present pledged to support him, no matter the cost. Hassan II then turned to Jouahri and instructed him to reveal to the ministers “how they will be dealt with.” This is how Morocco embarked on the IMF’s Structural Adjustment Program.

Blood and tears

So, it’s 1983, and Morocco is on the brink of default. Growth is barely 2%, inflation is at 10% (5% in 2023), and the public deficit is close to 12% (4% in 2023). Two years earlier, drought levels had reached a record high.

he depletion of foreign reserves left the state unable to import even a single barrel of oil. « We couldn’t even pay the ships docking in Casablanca to unload their cargo of oil and other imported goods, » recalls former USFP Finance Minister Fathallah Oualalou

During the two prosperous years of the phosphate boom, the state generously granted a 26% salary increase to civil servants. Food subsidies accounted for 25% of operating expenses.

Meanwhile, energy prices continued their upward spiral in the wake of the 1979 oil shock. To maintain its spending trajectory, the state further increased its external debt, which reached 128% of GDP (80% today). Foreign exchange reserves were only enough to cover two days of imports.

It was simple: the depletion of foreign reserves left the state unable to import even a single barrel of oil. « We couldn’t even pay the ships docking in Casablanca to unload their cargo of oil and other imported goods, » recalls former USFP Finance Minister Fathallah Oualalou.

The painful prescription from the IMF was inevitable. It would revolve around the famous liberal triad of the Reagan and Thatcher years: deregulation, liberalization, and privatization.

The painful IMF prescription was inevitable. It centered around the famous liberal triad of the Reagan and Thatcher years: deregulation, liberalization, and privatization. The IMF granted Morocco an initial debt rescheduling (five more would follow).

Investment spending was sacrificed, civil servant salaries were frozen, and food subsidies were drastically reduced. The people tightened their belts, and Morocco, once hailed as a “dragon,” was caught up in its Third World fate. There was no longer any flexibility in public spending.

In exchange for its loans, the IMF imposed structural reforms. Long governed by a Jacobin, interventionist philosophy, the state was now injected with a massive dose of liberalism. In the midst of the Sahara War, the kingdom no longer had control over its own finances. The dirham lost 25% of its value, the banking sector was liberalized, and thus slipped from the heavy-handed control of the authorities.

Any distortion that could hinder the free development of the market and its invisible hand was eliminated. The sacred macroeconomic balances became an obsession. Even Hassan II’s grand dam policy slowed in its implementation. “The IMF’s goal was to completely disengage the state in favor of the private sector,” notes an economist.

Ten years of purge

After ten years of this shock therapy, Morocco woke up fully liberalized but completely groggy. The populations were the hardest hit

After ten years of this shock therapy, Morocco woke up fully liberalized but completely groggy. Due to cuts in investment budgets, growth slowed, as did public investment. In 1982, public investment represented 27% of GDP, but by 1994, it had fallen to just 20% of the nation’s wealth.

The populations were the hardest hit. Over the decade of the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), per capita income grew by only 1% per year. No longer the dominant employer it had been in the late 1970s, the state saw unemployment rise from 10% in 1982 to 13% in 1991.

Although the country’s competitiveness improved through reforms, and growth stabilized at an average of 4% during the ten years of the SAP, much of the wealth generated was absorbed by debt service, which was frequently rescheduled. The lack of investment in education infrastructure led to a noticeable decline in primary school enrollment, especially in rural areas.

The balance is sovereignty

The ordeal was harsh, but in the end, Morocco gradually regained its theoretical independence from its lender, the IMF. Adopting the principles of the Washington Consensus, the country joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) and attempted to specialize in order to secure a place in international value chains.

This period definitively marked the kingdom’s shift toward an openly liberal economy. This would later lead to the signing of numerous free trade agreements. More than anything, this liberal purge implanted in the minds of our leaders, much like in Christopher Nolan’s Inception, an obsession with macroeconomic balance.

For Jouahri, “macroeconomic balance is part of national sovereignty.” And everything must be done to preserve it

Jouahri was the guru of this new economic religion. In 2020, at the height of Covid, he stood against the possibility of using innovative monetary levers to provide a breath of fresh air to the economy. According to Jouahri, “macroeconomic balances are part of national sovereignty”. And everything must be done to preserve them.

This « Jouahri consensus » quickly spread throughout the entire political class. But it didn’t stop there. It permeated the technocratic structure, which now swore by controlled deficits, managed debt, 2% inflation, and a subsidiary role for the state. This shift in thinking, following the Structural Adjustment Program purge, conditioned the state to allocate the lion’s share of public investment to infrastructure—the only way to facilitate capital flow and, consequently, encourage private investment.

The collateral damage? Sectors like health and education suffered greatly from this favoritism. The reforms that were supposed to take place in these areas were neglected. The result: a Morocco filled with airports and highways, but with a Human Development Index that stagnates at 121st place out of 189 countries.

Crackdown on politics

« The Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) comes into play when a country’s sovereignty needs to be restored through negotiations with international financial institutions that use financial constraints to impose a set of directives, » explains Larabi Jaidi, senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South and former advisor to Youssoufi.

However, the neoliberal policies imposed by the IMF to make Morocco solvent, initially intended to be temporary, have become a second nature for the successive governments since 1993. More notably, the deep state saw these policies as a tool for depoliticizing economic decision-making. Party ideologies were cast aside; the only thing that mattered was the almost religious adherence to the neoliberal mantra driven by the IMF.

Even the leftist Alternance government, despite its principles, gave in by privatizing large public companies en masse. « The Alternance government, of which I was a part, continued this reform logic, which solidified during the reign of Mohammed VI. Our aim was to build autonomy from international financial institutions. We needed to control our macroeconomic framework to safeguard our sovereignty, » explains Fathallah Oualalou.

Politics vs. technocrats

This opposition between the political sphere, viewed with suspicion (even though it, too, has embraced the Washington Consensus), and the technocratic sphere, devoted to neoliberal dogmas, frequently surfaces in Jouahri’s discourse. In June 2012, in a moment of spontaneity, he referred to political parties as « Bakour and Zaâtar, » meaning brainless or foolish entities, during a press conference. He later apologized for this linguistic misstep.

However, this unexpected outburst speaks volumes about his mindset. In his interview with the IMF, he reiterates his view. For him, politics is a source of uncertainty. “We see it around the world, there is a disintegration of political elites (…) this disintegration means that the population no longer trusts what is political and public.”

Jouahri goes even further. From his perspective, the distrust of the political class leads to the legitimization of supra-political, unelected, and technocratic bodies. “Central banks,” explains the Governor of BAM, “have become centers of truth-telling. People trust what the central bank says more than what politicians say.”

Jouahri’s approach of « delegitimizing the elected official, who is nonetheless an essential element of pluralism and democracy, in favor of technocracy, is reminiscent of the ten years of the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), where, under the control of the IMF, the state followed the cold dictates of technocrats from abroad, with, as Jouahri seems to believe, total efficiency, » notes an economist.

This belief, deeply ingrained in Jouahri, manifests in his monetary policy. Against the advice of many politicians, the government itself, and economists, he raised the key interest rate three times between 2022 and 2023, stifling bank credit distribution and, by extension, productive investment. This had no directly noticeable effect on the inflation rate.

A sympathetic IMF?!

From the era of the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), Morocco inherited what can be called the « Jouahri doctrine« : a shift of economic decision-making away from politicians and into the hands of technocrats, alongside the sweeping liberalization of the market.

In this context, it’s no surprise that in his interview with the IMF’s Deputy Director, Jouahri offers some leniency toward the SAP. « I admit, » he says, « that the IMF showed intelligence and relative flexibility. Because back then, the rules were very strict—there were dual caps, one for government spending and another for bank credits—but to my recollection, we never fully met 100% of the criteria. That’s when I found that the Fund and its structures, meaning the council, showed both intelligence and understanding within the framework of what we were doing. »

He concludes, « When the IMF was convinced by the arguments, it didn’t hold dogmatic positions. » A tough claim to accept for the dozens of countries that suffered under IMF control, and foremost among them, Morocco and its population.

Written in French by Réda Dalil, edited in English by Eric Nielson