It’s easy to date the history of the protectorate: 1912 – 1956. But this is only an appearance, an official window-dressing. In reality, the story is longer and far more complex than you might think. When exactly did it all begin? The answer depends on the school.

Politically, as Abdellah Laroui puts it, « the Moroccan state ceased to exist in 1880″ (in L’Histoire du Maghreb), i.e. when an important event, the Madrid Conference, placed the kingdom under international control. Militarily, the country collapsed in 1844, the day after the Battle of Isly. Economically, it suffered increasingly severe recessions throughout the 19th century.

So, which date should we choose? Most historians agree on the symbolic importance of the year 1830: « It was here, with the arrival of France in Algeria, that Moroccan history took a definitive turn for the worse, » sums up researcher Mustapha Bouaziz. The sudden irruption of Europe and its procession of aggressive values (its armies, its politics, its economic system) plunged Morocco into a kind of purgatory. This was the year when the countdown to a full-fledged protectorate began.

When the north wind blew

The year was 1830, at the heart of a century in which the face of the world was changing. While the industrial revolution (railroads, road networks, subsoil mining, maritime development, war materiel, etc.) and economic growth were sweeping the Western world at full speed, Morocco was living in self-sufficiency, closed off and jealously inward-looking.

In the century since the death of Moulay Ismaïl, the country has seen no fewer than 20 reigns

From the inside, the country bubbles with the jolts of insane political instability. The reigning anarchy makes the former empire look like a man on the verge of a nervous breakdown. One sultan follows another at a frenetic pace. In the century since the death of Moulay Ismaïl, the country has seen no fewer than 20 reigns. Some sultans reigned for just a few months, while others, thanks to coups d’état and reversals of alliances, abdicated before regaining their throne several years later: Sultan Abdallah II alone accumulated six reigns interspersed with as many interludes.

Overall, the country was divided in two: the bled Makhzen (plains, ports, major cities) under the sultan’s authority, and the bled siba (mountains) in dissidence. The borders between the two Moroccos fluctuated according to the frequency and scope of the harkas, punitive expeditions led by the sultan himself.

The organization of social life is based on rules inherited from the Middle Ages. Agriculture, livestock breeding and crafts make up the bulk of economic activity.

The volume of internal trade is low due to the difficulty of transport: roads are non-existent and insecurity is such that the country resembles a series of enclaves. Travel is slow, costly and extremely dangerous. The towns are virtually self-sufficient in food, while the countryside is controlled by local tribes.

Social life is punctuated by cycles of famine and epidemic. Education is reduced to its simplest expression (religious) and remains confined to the medersas-mosques. And the only medicine available is traditional, based on herbs and miracle products.

The state is the sultan

What about the state? It exists, of course, but in a configuration far removed from the schemes then in vogue on the other side of the Mediterranean. From the hajib-chambellan to the vizier of the sea (equivalent to a Minister of Foreign Affairs), via the amine des oumana (Minister of Finance) and the wazir chikayate (Minister of Justice), all have their bniqas-offices inside the palace.

The sultan is the state. It is he who convenes ministers and advisors in turn, rarely together, and it is he who appoints and controls his representatives in the deep country, the caïds and pachas

This leaves little room for doubt as to the nature of the political system. The sultan is the state. It is he who convenes ministers and advisors in turn, rarely together, and it is he who appoints and controls his representatives in the deep country, the caïds and pachas. Of course, this amalgam of state and sultan has a terrible consequence: when the king is fighting away from his palace, i.e. half his time, the entire state is practically at half-mast, and the whole country is left to its own devices.

This brings us to another important point, which in itself explains the extreme vulnerability of the Cherifian kingdom: the army. Apart from the traditionally loyal factions (the Bukhara, the Udaya, etc.), the bulk of the troops were provided by what might be called « war intermittents »: occasional fighters who might take part in a harka before returning to their respective tribes at the end of the expedition.

So it’s easy to understand why this army, with its uncertain form, uncertain motivation and fluctuating numbers, lost virtually every battle in which it was involved during the 19th century.

The poor pay for the rich

Now let’s look at the sinews of war: money. Here, too, we’ll see how the organization of the kingdom’s « financial system » was at the root of its asphyxiation and led straight to its being placed under protectorate.

With a rich but largely unexploited subsoil (rock salt, copper), the main resources were reduced to taxes and customs duties at the ports. Between the Makss, the Ma’ouna, the Naïba, the N’foula and the Jiziya, duties and taxes were so numerous that they were the primary source of popular uprising.

Apart from certain guilds (the tanners in Fez), there were no unions and no means of countering arbitrariness. Dissent became the rule. An angry citizen or tribe is just one more small part of Morocco to tip over into the bled siba and form a new pocket of resistance to the authority of the central « government ».

Taxes are neither generalized nor equitably distributed. The Chorfa, tribes allied and loyal to the sultan – in short, part of the local bourgeoisie – were exempt. It’s almost a cliché: the poor pay for the rich

The phenomenon is all the more frequent as taxes are neither generalized nor equitably distributed. The Chorfa, tribes allied and loyal to the sultan – in short, part of the local bourgeoisie – were exempt. It’s almost a cliché: the poor pay for the rich. But, as researcher Mustapha Bouaziz reminds us, « even the rich risk losing their property at any moment if they provoke a blood feud with the sultan« .

The practice of taxation functions at best as a compensation fund, at worst as a gigantic legal racket. When the cities, once flourishing thanks to the caravan trade, were suffocated by the flood of European settlers, the Makhzen turned to the already impoverished countryside to ransom the tribes with new taxes. It’s easy to imagine the social climate at the time, with ports hanging on Europe’s every word and the countryside on the brink of general insurrection.

A single objective: to gain time

In a Morocco that looks like a ticking time bomb, foreign trade and import-export activities remain an interesting window of opportunity. Probably the only one. But it is threatened by two recurring phenomena: the Sultan’s monopoly and the protection afforded to European interests.

The sultan more readily grants approval to Jews, to the detriment of Muslims. In his eyes, Jews posed no political threat and could therefore accumulate more wealth », analyzes Mustapha Bouaziz

The sultan’s monopoly (traders must sign a dahir of approval-delegation signed by the sultan, and may not bequeath any accumulated assets) is a means of controlling the enrichment of Moroccan subjects. « The sultan more readily grants approval to Jews, to the detriment of Muslims. In his eyes, Jews posed no political threat and could therefore accumulate more wealth« , analyzes Mustapha Bouaziz.

The protection granted to Europeans, first to British and French traders, then to all Western countries, created an endless series of disorders: the exemption from taxes considerably reduced state revenues, the massive arrival of European products killed off the embryonic local industry and devalued the national currency. Not to mention that the protection extended to the employees and Moroccan relations of these same Europeans is ultimately a safe-conduct that offers thousands of subjects the possibility of escaping financially, and even legally, from the authority of the sultan.

The kings who succeeded one another throughout the 19th century tried, each in their own way and with varying degrees of success, to contain the evil. Threatened by both local dissent and foreign incursions, forced to cope with a dying economic system, they mostly tried to play for time. The international context helped. For a long time, Europe hesitated between two possible attitudes: the English method, based on a policy of « comptoirs » (trading posts), giving exclusive priority to commercial interests, and the more « voluntarist » French method (gentle occupation, using military fortifications, institutional penetration and economic control). Not to mention the Spanish method, which was bellicose or even simply brutal.

Colonization, instructions for use

This exsanguinated Morocco, in shambles, completely disjointed, incapable of getting back on its feet, greatly whetted the appetite of its European neighbors, and indeed of the entire Western world. It’s not for nothing that, when the time comes to discuss the « Moroccan problem » in Madrid, twelve Western countries – an impressive total – are represented. Alongside immediate neighbors France and Spain, they included countries such as Austria, Norway, Italy and even the distant United States.

All have flocked to Madrid to share in the Moroccan cake. Morocco, the first country concerned, was under-represented and arrived on D-Day without any concrete proposals, ready to ratify whatever the foreign powers had proposed.

Historian Henri Terrasse writes: « The Belgians were setting up economic enterprises in Morocco, the United States was thinking of buying the Perejil islet (editor’s note: the same islet that provoked the violent Morocco-Spanish crisis more than a century later, in 2002), Germany began by financing the explorations of Rohlfs and Lenz and, under the guise of a peaceful settlement, planned to increase its presence in Morocco (in Histoire du Maroc) ».

Classically, European penetration used three instruments. Sociological exploration via explorers’ missions (Eugène Delacroix, Pierre Loti, etc.), first in the north and along the coast, then in the deep country, enabled the most accurate possible radioscopy of Moroccan society to be established. Economic supremacy has created a new local order and brought the kingdom under the control of a consortium of European banks. And military strikes destroyed the few pockets of resistance and made the sultans listen to reason.

The kingdom’s misfortune was that its decline coincided in time with the emergence of a new ideology: colonialism. This was the dominant trend of the time. So much so that even an intellectual above all suspicion, such as the poet Victor Hugo, uttered a famous phrase: « God is offering Africa to Europe. Take it. Solve your social problems, turn your proletarians into owners« .

Ali Benhaddou’s book, L’Empire des sultans, published by Riveneuve, is packed with colonialist gems. In addition to Hugo, the author quotes the astonishing race theorist Dr. Mauran: « If the pure Moor type is often found, with its matte complexion, busted nose, lively black eyes, slightly curling beard, large, widely spaced teeth, high stature, a race of prey par excellence, there are, alongside it, types that confuse and prove the crossing, the bastardization of the primitive race, indecisive, thick and heavy types, mulattoes of all degrees ».

The same Mauran, decidedly inexhaustible, also explains the unease of the « indigène » in the face of modernity: « They are still far from us, as far as the past, which surrounds them with an atavistic network. Many have traveled and know Marseilles, London, Paris and Egypt. In their astonishment at the spectacle of our modern life, there was a touch of superstitious terror, and when we invite them to enter the path of progress and civilization, they feel dizzy, as if faced with an unfathomable abyss where they fear sinking body and soul« .

The Tharaud brothers, who were long among Marshal Lyautey’s advisors, don’t mince their words when they give their take on the Moroccans: « Arrogant, fanatical, corrupt, corrupting, jealous of each other, always quick to criticize and unwilling to recognize the services they have been rendered. What they do today is just the same as what they did yesterday. A lot of luxury, no invention, too lazy to conserve, too untalented to invent« .

France-Spain: two gendarmes for the kingdom

If the winds of colonialism have swept away reasonable people and brilliant humanist minds, giving rise to appalling theories on the inequality of races, it’s because it has always draped itself in a civilizing mission. To colonize is to develop. The concept is part of national doctrine in all newly industrialized European countries. The idea was to exaggerate the features of the future colony, portraying it as a rich but undeveloped country dominated by lawless barbarians. The recipe worked, and public opinion embraced the views of its leaders.

After a long struggle against the vetoes of Great Britain and Germany, France and Spain took advantage of the internationalization of the Moroccan problem to definitively occupy the field. The Cherifian fruit was ripe, and threatened to fall at any moment in the late 19th century.

The sultans had accumulated enough debt with European banks: to pay tribute for lost wars, compensate for the drying up of the tax windfall… and maintain their lavish lifestyle (Moulay Abdelaziz, who reigned between 1894 and 1908, even set records for wasteful spending). The economic collapse alone justifies the sealing off of the Moroccan administration.

France and Spain logically shared the kingdom in a kind of concession-delegation offered by all the Western powers. If Germany and Great Britain ended up abdicating in favor of their two southern neighbors, it was with the guarantee that France and Spain would secure the commercial circuits on Moroccan soil. In short: a developed Morocco, with safe roads and modern means of transport, was the surest way to offer the economic added value so coveted by Europeans.

It was this pattern that led Morocco, after centuries of independence, to officially capitulate in 1912. Already on the ground, its hands and feet tied, the double protectorate imposed on it even appeared, ironically enough, to be the only way to « save » it.

A Sultan’s words. « I want to go and rest in France… »

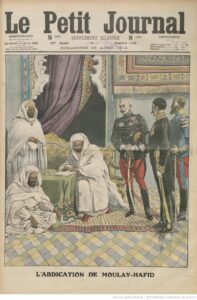

On the circumstances surrounding Moulay Hafid’s signature of the protectorate treaty, Ali Benhaddou reports two juicy anecdotes in L’empire des sultans.

« Moulay Hafid, the traditionalist, was deeply shaken. Having come to power as a symbol of resistance to foreigners, he couldn’t accept that he was the sultan of the French. Obsessed by this gloomy thought, he asks his interpreter and diplomatic adviser, Kaddour ben Ghabrit, an erudite, competent, great servant of France and future director of the Muslim Institute of Paris:

– Why are the French staying on the Moroccan coast?

– To maintain order and security, » he replied.

– I understood that in the time of my brother, who was a ruler without strength, but I’m capable of maintaining order in my state all by myself.

– The French will realize that this is only a temporary occupation, » adds the adviser.

Moulay Hafid looked at him for a long time, nodded and said:

– When Allah created the Earth, He also said that this creation was provisional!

Won over by skepticism and subjected to strong pressure, Moulay Hafid first protested, threatened to abdicate, then, on the morning of March 30, 1912, finally signed the Treaty of Protectorate. On the last day of his reign, he resignedly declared: « I would like to go to France to find peace and serenity ». Which he did on the spot ».

Timeline. Key dates

–1830. France occupies Algeria and has difficulty concealing its Moroccan ambitions. Lyautey, architect of the protectorate, once said: « Whether we like it or not, Morocco is a firebrand on the flanks of Algeria and, unless we evacuate Algeria, we will inevitably have to intervene there, as its anarchy has close repercussions on our authority and interests in Algeria ».

– 1844. Moulay Abderrahmane loses the Battle of Isly to France. Only the particularity of the international context delayed the occupation of the country. But trade treaties multiplied, opening up the economy to the progressive domination of several Western powers (Great Britain, France, Portugal, Spain)

– 1845. Signature of the Treaty of Lalla Maghnia, establishing the Moroccan-Algerian borders. With Algeria under French administration, the kingdom was forced to cede part of its eastern territory.

– 1851. Famine in Morocco. Two vessels flying the French flag anchored in the port of Salé. Loaded with wheat, they were immediately pillaged. France bombarded Salé in retaliation.

– 1860. Mohammed IV loses the battle of Tetouan against Spain and appeals to Great Britain to delay the occupation once again. But he was obliged, in return, to pay tribute to his Spanish victors: a large sum of money which took him two years to collect, during which time Spain occupied and fully controlled the Tetouan region.

– 1880. Moulay Hassan 1st unwillingly ratifies the agreements of the Madrid Conference, attended by twelve Western powers. This marked the beginning of the economic protectorate.

– 1902. The Comptoir national d’escompte de Paris (CNEP, a banking giant and forerunner of BNP Paribas) invests in Morocco, backed by the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas. The kingdom’s entire financial system changed not only its face, but also its hands, passing from amines-comptables to European bankers.

– February 1912. One month before the dual Franco-Spanish protectorate became official, European banks founded the « Compagnie Générale du Maroc ».

An era, a world. The revolutions of the 19th century

Two major events left their mark on the world during this century of upheaval. The Industrial Revolution and colonialism. The two are closely linked, since the industrialization of the economy rapidly created a shortage of raw materials, which opened the door to the conquest of new, untapped markets: the colonies.

Great Britain was, of course, the pioneer, developing its economy and dominating the world from the end of the 18th century. It was followed by the rest of the European powers throughout the following century.

Colonialism seemed a natural outlet, a legitimate need. For the first time in human history, economic growth became as sure a means of conquest as military might. In a world divided in two (the powerful and the colonized), Morocco could hardly escape its fate.

After a slow descent into hell, it joined the long pack of the dominated. As for the belated nature of colonization, this was more the result of a miracle (the interminable quarrels between the European powers over the sharing of the Cherifian « cake ») than of any internal resistance.

Selection. The ideal bibliography

- Charles de Foucauld (Reconnaissance du Maroc, 1888)

- Pierre Loti (In Morocco, 1890)

- Charles-André Julien (Histoire de l’Afrique du Nord, 1931)

- André Maurois (Lyautey, 1935)

- Henri Terrasse (History of Morocco, 1949)

- Brahim Boutaleb (Maâlamat Al-Maghrib and History of Morocco, 1967)

- Abdellah Laroui (L’histoire du Maghreb, 1970, and Les Origines sociales et culturelles du nationalisme marocain, 1977)

- Germain Ayache (Études sur l’histoire du Maroc, 1979)

- Mustapha Bouaziz (Moroccan nationalists in the 20th century, Chapter 1, PhD thesis, 2010)

- Ali Benhaddou (The Empire of the Sultans, Chapters 1 and 2, 2010)

Written by Karim Boukhari, Edited in English by S.E.

Vous devez être enregistré pour commenter. Si vous avez un compte, identifiez-vous

Si vous n'avez pas de compte, cliquez ici pour le créer