With the global economic slowdown, oil demand has been sluggish for several weeks. The price per barrel has dropped to its lowest level in nearly three years, falling below the $70 mark on Tuesday, September 10, and Wednesday, September 11. According to experts, this decline is mainly due to reduced economic activity in China and the United States, the world’s two largest oil consumers.

This trend even prompted the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to lower its forecasts. In its monthly report published on Tuesday, September 10, the organization now estimates that global oil demand will increase by 2.03 million barrels per day in 2024, compared to a previous forecast of 2.11 million barrels the month before.

A (relative) price decrease

This steep drop in oil prices is not without impact on fuel prices at the pump. Fuel prices have been declining for a few weeks around the world, including in Morocco. As recently as Monday, September 9, gasoline prices fell by around 30 centimes to approximately 11.77 dirhams per liter at various distributors, while diesel prices dropped by about 20 centimes, settling at around 13.67 dirhams per liter. Nevertheless, the reduction in prices remains modest compared to the decrease in global oil prices.

Several factors can explain this situation. For one, the exchange rate of the dollar against the dirham has increased in recent weeks, which somewhat offsets the effects of the lower price per barrel.

Another key factor to consider is the time lag necessary for fluctuations in oil prices to be fully reflected in pump prices. The final price paid by the consumer results from a complex calculation that involves multiple factors.

These include the delay between when foreign refineries purchase the crude oil and when they store the refined products. International transport networks also require some time to handle the fuel shipments and deliver them to distributors at Moroccan ports.

“If we simply followed the dollar market, we could have expected a drop of around 1 dirham in the next six weeks”

Finally, the time needed for distributors to store the refined products and deliver them to gas stations must be accounted for. All these factors contribute to a delay of about six weeks, according to Amine Bennouna, a professor at Cadi Ayyad University in Marrakech and an energy researcher.

“If we simply followed the dollar market, we could have expected a drop of around 1 dirham in the next six weeks. However, during this period of decline, the dirham has depreciated against the dollar. As a result, it is possible that in the next six weeks, prices might decrease by a few more centimes, but they will only fall slightly below 12 dirhams for diesel” explains Amine Bennouna.

A new tolerance threshold

However, the researcher explains that pump prices could have dropped even further if distributors had not simply increased their margins in recent years.

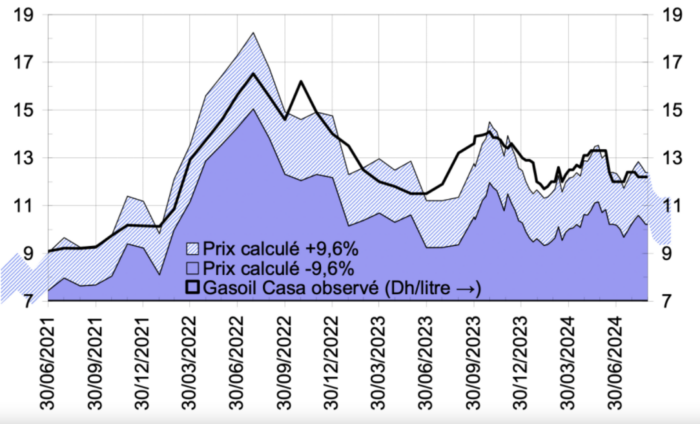

By taking into account fluctuations in oil prices, the dollar, and the time required for these changes to be reflected, the researcher developed a calculation model with a tolerance range of nearly 10%—both upward and downward—between June 2021 (the start of the energy crisis) and June 2024. This model helps establish a « theoretical price range » to compare against the diesel prices set by distribution companies in Morocco (see infographic).

This calculation model shows that during the energy crisis (from 2021 to 2023), when oil prices soared, pump prices remained within the middle of the tolerance range without ever falling below it. However, since the second quarter of 2023—a period that coincides with the start of the « return to normal » and the downward trend in international oil prices—pump prices in Morocco have continued to fluctuate « at the top » of the tolerance range, even exceeding it at times.

Distributors are taking advantage of a new « acceptability threshold » among consumers, who have long been accustomed to paying steep prices to fill up their tanks

According to Professor Bennouna, this situation results from an increase in distributors’ profit margins since the return to normalcy in oil prices. Distributors are taking advantage of a new « acceptability threshold » among consumers, who have long been accustomed to paying steep prices to fill up their tanks.

“Distributors now know that Moroccan drivers and transporters have become accustomed to high pump prices. Not long ago, a liter of diesel cost 14 or 15 dirhams, and everyone just wanted it to drop to 12 dirhams. Today, although the pricing method used before 2022 would yield a significantly lower distribution price than 12 dirhams, we see that margins continue to increase by capitalizing on the new tolerance threshold of consumers,” explains Amine Bennouna.

Free competition, really?

In theory, there’s nothing illegal about this situation—unless collusion to increase these margins were to be proven. Since the state ended its control over diesel and gasoline prices in December 2015, distributors have been free to set their own prices and margins and allow competition to play out. A simple principle that, in practice, has not been respected by these companies, who have been accused of engaging in illegal price-fixing given the record profits generated since the market was deregulated.

It took nearly four years of waiting and a change in leadership at the Competition Council for the authority to finally take action against oil operators.

As a settlement, the companies were collectively fined « an amount totaling 1.8 billion dirhams, for all the concerned companies and their professional organization, along with a series of behavioral commitments that these companies and their organization have agreed to in order to improve competitive practices in the hydrocarbons market in the future, and to prevent competition risks for the benefit of consumers » according to the Council’s statement released on November 23, 2023.

“The distributors have made huge profits since deregulation and managed to increase their margins. They could have challenged the fine in court, but they rushed to pay it to close this chapter”

But since the fine, no major changes have been observed in pump prices, except for the fact that price adjustments—previously made almost simultaneously across all distributors—are now happening with a few days and a few centimes of variation.

“The distributors came out on top from this episode. They have made huge profits since deregulation and managed to increase their margins. They could have challenged the fine in court, but they rushed to pay it to close this chapter” explains Amine Bennouna, lamenting that the deregulation of the sector under the Benkirane government was not conducted « intelligently, » as it lacked proper « market regulation. »

According to the researcher, this could have been solved by creating a regulatory body dedicated to the sector, similar to the National Telecommunications Regulatory Agency (ANRT), which ensures compliance with fair competition rules in the telecommunications industry.

“The Competition Council alone cannot oversee everything; it is tasked with thousands of cases at once. You cannot closely monitor oil companies, wholesale markets, restaurants, notaries, and so on, all at the same time.

The ANRT is a great example: Maroc Telecom, Inwi, and Orange pay tens of millions of dirhams each year for even the slightest violation because they are always under scrutiny. You won’t find identical offers between two operators without it being penalized,” he notes.

And he concludes: “Since Covid, we’ve realized that we need a protective state. The era of rampant capitalism and neoliberalism is over; market competition alone cannot solve everything.”

Despite the 1.8 billion dirham fine imposed by the Competition Council last year, oil companies continue to profit from the latest energy crisis. The fluctuations in oil prices over the past few years appear to have set a new “threshold of acceptability” for consumers… pic.twitter.com/HePHiPtKS9

— TelQuel (@TelQuelOfficiel) September 20, 2024

Written in French by Safae Hadri, edited in English by Eric Nielson