It is the reform that carries all hopes. Civil society has been awaiting it for at least fifteen years, while politicians, more hesitant, have referred to it on multiple occasions. Salvation finally came in the form of a statement from the royal cabinet, published on the evening of December 23, instructing the government to inform the public of the progress of the reform following royal arbitration and that of the Supreme Council of Ulema.

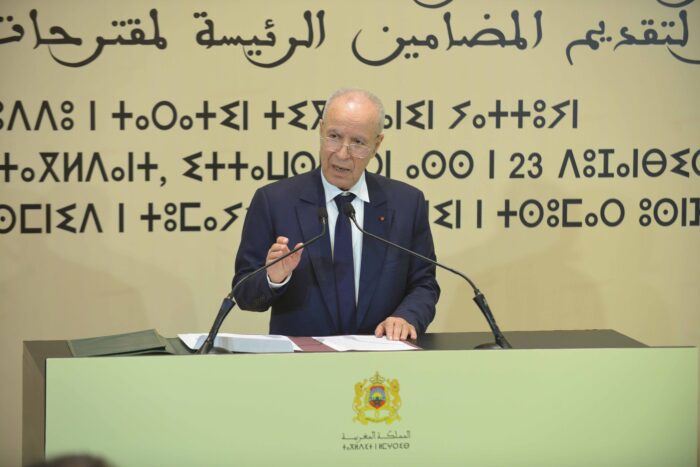

Without delay, a press conference is held the next morning in the presence of the head of government. After a speech by Ahmed Toufiq, Minister of Habous and Islamic Affairs, who revisited the role and considerations of the Supreme Council of Ulema, Abdellatif Ouahbi, Minister of Justice, outlines the key conclusions of the reform.

To understand the significance of these long-awaited announcements, we must go back to July 30, 2022. That evening, the Moudawana was the first topic addressed by the sovereign in his Throne Speech. At the time, nothing indicated that a reform of the Family Code was among the national priorities.

The political sphere was caught by surprise, while civil society organizations felt relief—the Throne Speech signaled a royal push. « We call for the implementation of constitutional institutions concerned with family and women’s rights, and we request that national mechanisms and legislation dedicated to promoting these rights be updated, » the sovereign urged.

Kickoff

Twenty years later, these vivid memories fuel questions among supporters of a new Family Code: while the royal directives are clear, should they expect a repeat of the 2004 scenario? Or can it be avoided precisely because, this time, the royal initiative comes before the public debate? In 2004, a commission composed of about fifteen ulema, magistrates, and researchers led the reform—who will take the reins this time?

The answers come a year later. On September 26, 2023, while national news is still dominated by the Al Haouz earthquake, a statement from the royal cabinet announces that a letter from the sovereign has been sent to the head of government. The Constitution stipulates that the government holds the authority for “legislative initiative.” Thus, the reform process is placed under the leadership of Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch. The directives are clear and precise: the approach will be participatory, taking into account societal developments while maintaining the framework of “values of justice, equality, solidarity, and coherence, as promoted in the authentic sources of the Muslim religion, as well as the universal principles outlined in the international conventions ratified by Morocco,” as stated in the royal letter.

Accordingly, the head of government leads a body composed of the Minister of Justice, the presidents of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and the Supreme Judicial Council. The Supreme Council of Ulema, the National Human Rights Council, and the Ministry of Solidarity, Social Inclusion, and Family are also invited, per the sovereign’s request, to be closely involved in the work of this commission. Their role is to conduct “consultations” and “expanded hearing sessions” with the country’s social, civil, political, and institutional fabric. Based on these discussions, the commission is tasked with submitting amendment proposals to the king “within a period not exceeding six months.” The countdown has begun.

On September 27, the day after the royal letter was received, the commission holds its first meeting at the government headquarters, bringing together representatives of judicial institutions: Mohamed Abdennabaoui, Aziz Daki, and Abdellatif Ouahbi. A second meeting follows two days later, this time without Aziz Akhannouch. His Minister of Justice sets the tone: “We will listen to civil forces and government officials, and we will try to listen to everyone to agree on a set of changes,” Abdellatif Ouahbi tells the press on the sidelines of the meeting. The work can now begin.

“We were heard”

The hearing sessions officially began on November 1, 2023. Until the end of December, the commission met several times a week with the relevant stakeholders: institutional representatives, union leaders, and political figures. As for civil society, our sources indicate that nearly 1,500 associations, often organized into coalitions, were represented before the commission.

“This time, no red lines were drawn, and all proposals were listened to attentively”

According to various testimonies gathered by TelQuel, the tension surrounding the issue in public opinion contrasts sharply with the calm atmosphere that prevailed during these hearings. « We were told, ‘We are here to listen to you,’” said Nouzha Skalli, former Minister of Family and president of the think tank Awal Houriates, in an interview last October. She added, « They were not there to challenge or debate our proposals but to hear them, because they acknowledged that, as civil society, we understand the realities and struggles that women face. »

For one to two hours, the commission carefully recorded the proposals submitted by each organization. « I must also say that I felt immense pride in seeing all these feminist civil society groups speaking with a unified voice, without making concessions. In 2004, even when advocacy work was being done, discussing equality in inheritance was unthinkable without being accused of blasphemy. This time, no red lines were drawn, and all proposals were listened to attentively, » the former minister continued.

This sentiment seems to be shared by many representatives of civil society organizations that participated in the process. « There were no questions from the commission, except for a few purely technical interventions to better understand our proposals. For example, we advocate for the prohibition of polygamy. We were then asked whether this ban should apply even in cases where the wife is unable to conceive, » says Amina Lotfi, president of the ADFM. This process is also an opportunity for civil society groups advocating for the most progressive reform possible to showcase work that has been carried out over many years, drawing inspiration from the constitutional achievements of 2011 and the Ijtihad effort encouraged by the sovereign.

The PJD against everyone?

Within political parties, internal organization was set up to prepare for these listening sessions. On the left, proposals were put forward that were said to have « unanimous support”: criminalizing child marriage, banning polygamy, recognizing children born out of wedlock through DNA testing, revising inheritance laws to allow greater flexibility in wills, and eliminating tâassib (forced inheritance rules).

After submitting two separate but very similar memorandums to the commission, the PPS and USFP took the initiative to form a common front to gain more visibility in the public debate. However, this alliance, which was meant to materialize through a joint event bringing together civil society and the youth wings of both parties, did not last long.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the PJD, the main opponent of the 2004 reform, faced much stronger internal divisions. The party of Abdelilah Benkirane, which threatened to organize a “million-man march” in the streets if certain « red lines » were crossed in the reform, was internally split between a conservative faction—led by the secretary-general—and a more progressive wing.

« At the time, the PJD, the MUR, and all civil society groups affiliated with the party formed a united front. This time, during the drafting of our memorandum, we faced disagreements between the PJD and the party’s women’s association, as well as between the PJD and the MUR, » said Amina Maelainine, a senior PJD member and part of the internal committee responsible for the memorandum, a few months ago.

The committee, composed of several members of the party’s general secretariat and chaired by Abdelilah Benkirane himself, unanimously agreed on two key points: religious principles must serve as the foundation of the reform, and certain issues stem not so much from the current Family Code but from its implementation. « However, some proposed amendments had to be put to a vote due to a lack of consensus. These are the most sensitive points of the reform that are now at the center of public debate. And following the PJD’s decision-making process, the majority—meaning the more conservative faction—prevailed, » Amina Maelainine continued. Among the disputed issues were polygamy, child marriage, and taâssib (forced inheritance rules).

Aside from the more progressive proposals from the left and the more conservative stances of the PJD and the Istiqlal Party, most of the political parties’ memorandums, reviewed by TelQuel, aligned on several key aspects of the reform, preventing the deep societal rift that had initially been feared.

A source close to the reform commission confirmed this: « The PJD often found itself isolated in its positions. Even Istiqlal called for changes regarding taâssib and lwassiya. This relative convergence between political parties and civil society, which was consulted throughout the process, helped ease tensions and debates within the commission itself. »

For Mehdi Mezouari, a member of the political bureau of the USFP, the alignment of political party proposals was not surprising: « I think political parties chose realism. They made proposals that align with our capacities and means. No one could afford to take an entirely radical stance, in one direction or the other. This is realpolitik. We have the space to reform and debate, but there are also fundamental principles that are already established and form part of the structure of the Moroccan state. That is how consensus is built, » he told TelQuel last October.

Cards on the table

After two months of consultations, the commission concluded this initial phase on December 29, 2023. It then had three months to compile the submitted proposals, deliberate on them, and draft amendments to be presented to the head of government, who would then forward them to the sovereign.

According to multiple sources consulted by TelQuel, neither political parties nor civil society engaged with the commission members after the hearing sessions ended. The commission continued its work behind closed doors, holding nearly three meetings per week. « There were comments and remarks from both sides, but the commission’s role was not to make arbitrations, » revealed a source familiar with the negotiations.

The Minister of Justice, Abdellatif Ouahbi, and Amina Bouayach, president of the CNDH, were identified as the driving force behind the commission’s progressive wing, while other members displayed more conservative positions—such was the case of Aawatif Hayar, who at the time held the position of Minister of Family and was dubbed « the enemy of women » by her critics.

“Ouahbi and Bouayach knew that the task was difficult and that they needed to be well-prepared to defend the most sensitive aspects of the reform”

« Ouahbi and Bouayach knew that the task was difficult and that they needed to be well-prepared to defend the most sensitive aspects of the reform, » confided a source close to the commission.

According to our information, Abdellatif Ouahbi took the initiative to form a task force within the ministry, responsible for studying and preparing arguments in advance for each of the positions he intended to defend. « On the issue of child marriage, he was uncompromising, » recalls an internal source. « He fought to the end for the abolition of taâssib and the introduction of mixed marriage. He constantly went back and forth between the internal committee and the commission meetings. At his request, arguments had to be developed, dismantled, and refined, ensuring responses to every possible objection raised against any amendment. »

According to our sources, the commission’s progressive wing viewed the 2022 Throne Speech and the royal letter as a strong argument: the sovereign had indeed set a reformist course. « At one point, negotiations had stalled, and progress seemed minimal. The issue was brought to the royal cabinet’s attention, and that’s when discussions resumed with more intensity, incorporating greater use of Ijtihad, » our contact revealed.

The commission remained on schedule. On March 30, nearly six months to the day after receiving the royal letter, it submitted its proposed amendments to Aziz Akhannouch. About ten days later, documents began circulating in WhatsApp groups and were picked up by several media outlets—allegedly excerpts from the commission’s proposed amendments, though their authenticity remained unverified. The PJD quickly reacted, denouncing amendments that it claimed were « contrary to the Islamic identity of the country. »

The controversy quickly faded, with no further credibility given to the documents’ authenticity.

On June 28, 2024, a statement from the royal cabinet announced that, under Article 41 of the Constitution, the sovereign had submitted « certain proposals » from the commission related to religious matters to the Supreme Council of Ulema, requesting a fatwa on them for « His High Appreciation. »

Their opinion was finally communicated at the end of 2024, during a working session presided over by King Mohammed VI on December 23, and made public the following morning in a press conference.

Ulema

The safeguards of the reform

« An anti-seismic structure »—this is how former Minister of Family Nouzha Skalli describes the reform process established by the sovereign. « From the royal directives to the Supreme Council of Ulema, passing through an unprecedented institutional debate that involved civil society and political parties, the process of drafting the reform is very solid. Those who try to shake the building will not succeed, » she comments.

Whereas in 2004, royal arbitration was a reaction to a deep rupture in public opinion, the method adopted twenty years later is designed precisely to prevent such a divide. On the one hand, it promotes a participatory approach, giving a voice to all organizations and structures that wished to express their views on the matter, regardless of political or ideological affiliation. On the other hand, the very composition of the commission reinforces this approach. « The individuals who make up the commission were not appointed by His Majesty as individuals but as representatives of institutions directly concerned with the reform, » notes Nouzha Skalli.

Finally, because all consultations took place in the presence of the Ulema, « whose opinion will give even more strength and credibility to the reform, » according to former Minister Yasmina Baddou. « The presence of the Ulema, in addition to their consultation by the sovereign, is highly political—it was necessary to send the message that they were there, » confirms a source close to the commission.

Since the Supreme Council of Ulema is the only authority authorized to issue fatwas, their opinion on a progressive reform will be difficult for political movements to challenge. « Once their opinion is given, it will not be up to the PJD or any other organization to dictate what is halal and what is not, » concludes Amina Maelainine, a senior member of the Islamist party.

Rights

Taâssib equality in inheritance, what is the difference?

A few years ago, the issue of equality in inheritance was only mentioned in hushed tones, triggering fierce opposition against anyone daring to utter the forbidden words. In 2024, things have changed significantly, as inheritance laws are now an integral part of the debate on reforming the Family Code.

While the toulout rule—where sisters receive only one-third of the share allocated to their brothers—comes directly from Quranic text, many scholars agree that the rule of taâssib stems from an interpretation of the text rather than a divine mandate.

Taâssib, as applied in the current Family Code, requires female heirs without brothers to share their inheritance with male relatives, often distant ones. This has led to tragic situations where women are stripped of their inheritance in favor of an uncle they may have never even known existed.

Controversy

PJD vs CNDH

Abdelilah Benkirane’s distrust of the progressive wing of the reform is well known, as he believes they are determined to distance the process from its religious foundations. « It seems to me that he sees a looming threat over the final draft of the proposal written by the commission. This threat does not only concern the content of the reform but also the functioning of the institutions responsible for drafting it, » political analyst Bilal Talidi, former editorialist of the now-defunct Attajadid, the PJD’s former media outlet, told TelQuel last March.

At that time, the former head of government made multiple media appearances criticizing the CNDH, whose president is known for her progressive positions. He condemned its involvement in the drafting process, arguing that one cannot be « both judge and party. » The PJD specifically referred to the memorandum prepared by the CNDH, which outlined its own proposed reforms to the Moudawana.

« Personally, as a democrat, I am in favor of debate. I think it is healthy to have proposals that contradict ours and to engage in real discussions to argue them. However, the problem arises when an institution is both a member of the commission and an active participant in the debate, » Amina Maelainine commented on the issue. « The CNDH is a constitutional institution that is supposed to represent the full diversity of opinions in society. The CNDH cannot, as it has done, act as the spokesperson for the so-called progressive camp while positioning itself against a more conservative viewpoint, which is also part of society, » the senior PJD member continued.

For its part, the CNDH has not issued any official response to these accusations. However, on social media, members of the council’s regional branches have denounced the PJD’s « lies, » emphasizing that the CNDH’s memorandum was drafted well before the commission’s work even began.

Written in French by Soundouss Chraibi, edited in English by Eric Nielson