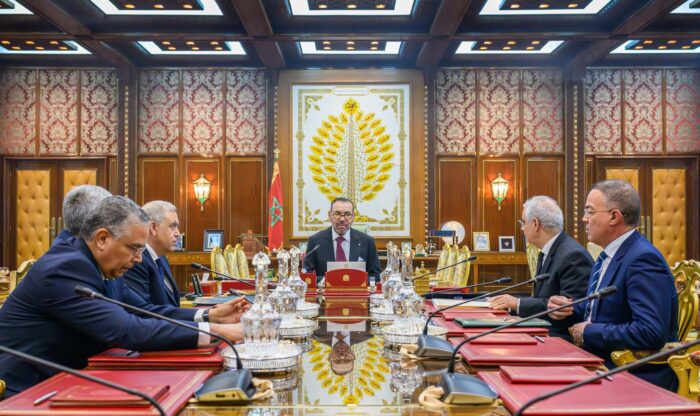

« We consider the current water shortage situation to be a structural problem. » This is how the Minister of Equipment and Water, Nizar Baraka, addressed the deputies on January 22 during a session at the House of Representatives. This speech came just days after the presentation on January 16 before King Mohammed VI, detailing the state of the kingdom’s water resources and an emergency plan implemented by the ministry to address the issue.

Among the urgent measures announced were the mobilization of resources at existing dams, wells, and desalination plants, the implementation of urgent water supply and distribution equipment, and, where necessary, potential restrictions on irrigation water or distribution flows. Already, the governors of certain regions have called on owners of hammams (traditional bathhouses) and car wash garages to close their businesses three days a week, from Monday to Wednesday.

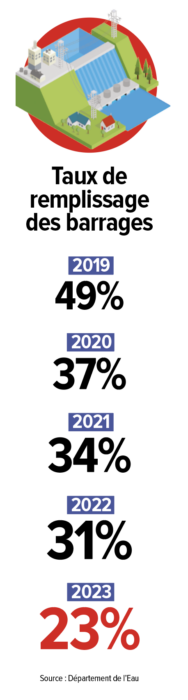

The situation is more than critical in the kingdom. From September 2023 to mid-January 2024, Morocco experienced a rainfall deficit of 70% compared to the average, and the dam filling rate was 23.2% versus 31.5% at the same time last year, according to Nizar Baraka. The Al Massira dam, the second largest in the country, which supplies Casablanca and Marrakech, was only 0.56% full as of January 31.

“Drought in Morocco is no longer considered a temporary issue; it has become the norm,” emphasized Fouad Amraoui, a professor-researcher in hydrology at Hassan II University in Casablanca, in an interview with TelQuel at the end of December. This was after several warning speeches by the minister in charge.

While all experts agree that climate change is a factor, it is not the only cause of this crisis situation, the effects of which are being felt both in agriculture and in the lives of citizens, who will now have to expect water restrictions and rationing in the coming weeks.

A problem that dates back

“Morocco has always been very vulnerable in terms of its water resources; it has always experienced climatic variability, exacerbated by climate change,” explains Mohamed Jalil, a climate and water resources expert and Secretary General of the Moroccan Federation of Consulting and Engineering, in an interview with TelQuel.

“Morocco is a country whose water resources are primarily meteorological; it depends on rainfall. This rainfall is known to be subject to climatic variations. In fact, the major dams are designed to store 4 or 5 years’ worth of floodwater,” adds the expert.

But “we shouldn’t place all the blame on climate change. Public policies also bear some responsibility,” he explains. “We have always said that Morocco is a semi-arid country, or even arid in some regions. The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) projections have also sounded the alarm, indicating that precipitation will decrease, and unfortunately, we haven’t taken these findings seriously in our public policies,” admits Charafat Afilal, former Minister Delegate for Water (2013-2018) under Minister Abdelkader Amara, in an interview with TelQuel.

However, the issue is not new. Experts consulted by TelQuel remind that Morocco has been experiencing a decline in its water resources for over thirty years. “The effects of climate change on water resources began in the early 1990s and progressively worsened throughout the decade, becoming predominant by the end of the millennium, even though people, including officials, did not realize that climate change was the cause,” explains Mohamed Bazza, a water resources expert, in an op-ed published on January 22 in our columns. And it is not for lack of having issued warnings repeatedly.

As early as the first year of his reign, King Mohammed VI was already alerting to the need for “rational management of water resources” in his Throne Speech of July 30, 2000, calling for “a review of water-intensive or drought-vulnerable crops” and “encouraging water-saving techniques and low-water-use crops.” The sovereign also called for “developing a modern approach to dam policy, mobilizing new resources in this area (…) and establishing the foundations of a water culture” among citizens, “considering water as a vital material and a scarce resource that must be preserved.” Water ressources were also the main theme of the King’s speech in his Throne Speech of July 2024.

“So, for more than twenty years, it has been declared clearly and explicitly that we are in very dire straits!”

One year later, during the organization of COP7 in Marrakech in October-November 2001, Morocco produced a report that also addressed water scarcity and drought. “So, for more than twenty years, it has been declared clearly and explicitly that we are in very dire straits!” reminds Mohamed Jalil. Yet, nearly a quarter of a century later, the situation has only worsened.

In November 2022, the World Bank published its report on climate and development, focused on Morocco. The findings are unequivocal: “Morocco is a region of high climate vulnerability and is one of the most affected countries in the world by water stress, as it is rapidly approaching the threshold of absolute scarcity set at 500 m³ (per person per year).”

With a population of over 37 million inhabitants, Morocco would need more than 1000 m³ of water per person per year to ensure an optimal level of comfort. The report also highlights that a 25% reduction in water availability across all sectors of the economy, combined with decreased agricultural yields due to climate disruptions, could reduce the kingdom’s GDP by 6.5%.

It emphasizes that “while investments in hydraulic infrastructure are crucial, they must be accompanied by reforms in the water sector and changes in consumer behavior.”

Hydrologist Fouad Amraoui adds: “The current water situation is concerning and uncomfortable, as not only can the dams no longer supply water to the majority of our irrigated areas, but the supply to urban domestic areas, which only account for 10% of the country’s total consumption, is no longer guaranteed everywhere as it was before.”

Delays and poor management

Although Morocco has been pursuing a policy of building large dams to harness its water resources since the 1960s, experts point to a lack of foresight regarding the depletion of these resources and, especially, the need to change our way of life and our needs, including in agriculture and industry.

“Economic needs are increasing, but the amount of water has decreased, so the supply/demand balance is not longer balanced,” says Mohamed Jalil. “Hydro-climatic phenomena are not abrupt like an earthquake; they come in an insidious, very slow, gradual manner. These are things we should have anticipated; it’s not as if the sky has fallen on our heads,” adds the expert, who believes that public policies should have taken a forward-looking approach. “We could have anticipated what is happening today at least 30 or 40 years ago.”

This view is shared by expert Mohamed Bazza: “There is no doubt that reaching this stage of crisis, and so quickly, is due to poor water resource management, the effects of which have accumulated over the past 20 to 25 years,” he emphasizes, noting that it is “shameful for Morocco to reach this stage in 2024, as it was possible to manage water scarcity without reaching a crisis, unlike countries that suffer from water scarcity at levels higher than Morocco but never reach a crisis stage.”

For former Minister Charafat Afilal, a lack of consideration for scientific data and long-term vision in public policies has clearly been missing in recent years. “The water sector requires scientific expertise to design public policies based on past statistics and future projections, in order to correct course and implement necessary measures,” she asserts.

“Technicians, engineers, and water experts understand this language. But users, and departments that use water, do not understand it. They wait for September for the rain to start. And if it doesn’t rain, they wait for January. Some decision-makers think this way too. But we cannot work like this. We need to work in a scientific manner,” she elaborates.

A lack of foresight also attributed to political timelines, which are out of sync with climatic timelines. “A political term does not align with the timeline of climate change or water management. This management needs to be done over the long term,” reminds Mohamed Jalil.

While there are integrated water resource management master plans (PDAIRE in French) established over ten years, “the term of a regional or municipal council president, or of a parliament or government, is shorter than the timeframe of the impact of their policies,” adds the specialist. He explains that a decision made today can thus have a negative impact in ten years. “That’s what has happened. Many governments have come and gone: Istiqlal, USFP, PJD… But they are too short-term oriented, and for this kind of thing, one must instead look at the long term. We need much more stable policies; that’s the role of the central state.”

Mohamed Jalil also points to the delay Morocco has experienced in treating and purifying wastewater, known as “non-conventional” water, which can be reused in agriculture or for watering green spaces and represents an alternative to “conventional” water sources like rainfall, on which Morocco remains extremely dependent. “Wastewater has been regarded in rhetoric as a resource, but unfortunately, it has never been truly believed in, unlike in countries such as the United States, Israel, or in Europe,” he emphasizes.

« I have always said that we needed to find an alternative to rainwater or groundwater, namely the reuse of wastewater. But no one took what I was saying seriously, as if it were unachievable.”

A “huge” loss for Morocco, as “the amount of wastewater that can be recovered in cities represents at least 70% of the water consumed,” notes our source. The reuse of wastewater was also among the solutions proposed by former Minister Afilal during her term, she emphasizes: “I have always said that we needed to find an alternative to rainwater or groundwater, namely the reuse of wastewater, for example in agriculture. But no one took what I was saying seriously, as if it were unachievable,” she defends.

“Now, this solution is back on the table. The ministry has set up an entire program focusing on this aspect, as well as on the issue of water loss in irrigation channels and drinking water networks, which reaches 50%,” adds the former minister.

« “If there is a delay, it is a delay in mindset. We have remained in the euphoria that Morocco is an agricultural and exporting power (and thus water-intensive), and we have completely forgotten that we are structurally an arid to semi-arid country.”

Another delay faced by the kingdom is in “mindset,” notes Mohamed Taher Sraïri, research professor at the Institut Agronomique et Vétérinaire (IAV) Hassan II in Rabat: “If there is a delay, it is a delay in mindset. We have remained in the euphoria that Morocco is an agricultural and exporting power (and thus water-intensive), and we have completely forgotten that we are structurally an arid to semi-arid country. The proof is that today, we are still bombarded with advertisements announcing an increase in Moroccan exports. Meanwhile, cities are facing potential water shortages.” He thus hopes for a “wake-up call” and collective “awareness”: “I am especially worried for future generations. What will we tell them in twenty years, when they might not even have water to drink?”

« Green Morocco plan », red flag

The crisis is also linked to the intensification of agriculture over the past twenty years, particularly associated with the Green Morocco Plan (PMV, Plan Maroc Vert) launched in 2008. Led by the current Head of Government, Aziz Akhannouch, who was then Minister of Agriculture, the PMV focused on diversifying crops, modernization, and intensification with the aim of producing better and, most importantly, more, to export a maximum of tomatoes, citrus fruits, and other agricultural products abroad.

While this decade-long plan resulted in nearly 40 billion dirhams in exports in 2019, compared to 14.2 billion in 2009, it is now heavily criticized by experts who attribute a share of responsibility for the current water crisis to it. The case of watermelons planted in Zagora, a dry region facing severe water shortages and which has experienced “thirst riots” several times in recent years, is emblematic.

“We have created an agriculture, especially in recent decades, that was not suitable. The Green Morocco Plan was the turning point because we moved towards an agriculture where irrigation had to be forced at all costs.”

“We have created an agriculture, especially in recent decades, that was not suitable. The Green Morocco Plan was the turning point because we moved towards an agriculture where irrigation had to be forced at all costs. As a result, we have exhausted the fragile resources that could have been our backup to face what we are experiencing today. Unfortunately, the backup resources are depleted; we have exhausted them,” laments Mohamed Taher Sraïri.

He elaborates: “When a new private irrigation area is established, people dig wells and start pumping, which inevitably accelerates the pumping of fragile groundwater.” Thus, “the initial increases in agricultural production observed with the launch of the Green Morocco Plan were due to nothing more than the mobilization of fragile groundwater, which is now exhausted.”

Overexploited, the water table in the Souss-Massa region was the first to be completely depleted, ‘which, in fact, led to the necessity of desalinating seawater to save the city of Agadir,’ reminds Mohamed Taher Sraïri.

Overexploited, the water table in the Souss-Massa region was the first to be completely depleted, « which, in fact, led to the necessity of desalinating seawater to save the city of Agadir, » recalls the agronomist. « It’s not even for agriculture anymore, but for urban activities, so that citizens can wash their hands, so that a tourist can go to the pool, etc., » he specifies.

« Whether for the agriculture department or the water sector, these sectors have developed beyond their capacities, » admits former Minister Charafat Afilal, highlighting that « we have crossed the red line of the country’s water capacity. » While she acknowledges that the Green Morocco Plan has indeed encouraged the country’s development, agricultural production, job creation, exports, and the influx of foreign currencies into the kingdom — which is « good for the national economy » — it should not have been done « at the expense of the water resource and the sustainability of this resource. However, the expansion of private irrigation has exceeded our capacities. »

“In Morocco, we are paying dearly for having allowed, with abundance, certain investments, such as those in orange cultivation in the South, for example.”

According to another former water minister interviewed by TelQuel, who preferred to remain anonymous, “we should also consider the experiences of other countries facing the same issue.” For example, Chile “is paying dearly for the choice of certain types of agriculture, such as avocado cultivation, which has significantly impacted the country’s water resources,” he explains.

“In Morocco, we are paying dearly for having abundantly allowed certain investments, such as those in orange cultivation in the South. If there were no desalination plant in Agadir, there would be no life there today,” emphasizes the former political figure.

This observation is shared by climate and water resources expert Mohamed Jalil: “The agricultural policy is questionable on several points: do the varieties we have planted match the climatic, physical, and soil conditions of the regions? We cannot practice agriculture just anywhere!” he insists.

Another flaw in the system noted by the specialist, and not a minor one, is: “The person who designed the public policies also evaluated them. The Green Morocco Plan was created by the Ministry of Agriculture, and it was also the Ministry that assessed it. It’s like being both the judge and the defendant in a trial.”

For him, the damage could have been avoided: “If the Green Morocco Plan had been evaluated neutrally and objectively a long time ago, we could have predicted a regression of resources, a problem of water scarcity, pollution, and territorial imbalance of the resource, and we could have addressed many issues. Instead, we closed our eyes.” Until when?

Platform. Nechfate.ma simplifies climate change

If you’re struggling to keep up with climate change news in Morocco, Nechfate, which literally means « it’s dried up, » is for you. This Moroccan platform gathers and shares key information on the subject within Morocco.

“We publish short articles to help improve understanding of this issue, including explanations of climate science, impact analysis, and discussions on possible policy responses. We provide Moroccan citizens with the tools they need to understand the stakes related to climate change and the means to address them,” explain its founders in the site’s introduction.

These founders, young Moroccans who are engineers, economists, agronomists, and legal experts, aim to use their skills and knowledge to raise awareness about the “concrete impact” of global warming on Morocco.

They also offer solutions “that are or could be implemented to protect our country,” particularly against water stress. For example, in an article about desalination, the platform questions the financial, energy, and environmental costs of this “promising technology.” Another article provides a detailed overview of national greenhouse gas emissions. “Our goal is to shed light on this topic and create real momentum,” say its founders.

Written in French by Anaïs Lefébure and Ghita Ismaili, edited in English by Eric Nielson