It’s becoming a recurring issue. Since Aziz Akhannouch took office, the national economy has been persistently destroying jobs.

It’s surprising for a government with techno-liberal leanings and a business-oriented mindset that led many to hope for an economic boom in Morocco. However, that is not the case so far. Clearly, an understanding of business mechanisms is not enough to get Morocco back to work.

Overflowing with confidence during his 2021 election campaign, Aziz Akhannouch promised Moroccans the creation of 200,000 jobs annually, along with a 4% GDP growth.

Reality has contradicted these forecasts. In 2022, the first full year of the new Executive’s term, the economy lost 24,000 jobs. In the second year of the term, 2023, the economy again eliminated 157,000 more jobs. According to the Executive’s projections, the shortfall for Morocco after two years of the RNI/PI/PAM majority is 581,000 net jobs lost.

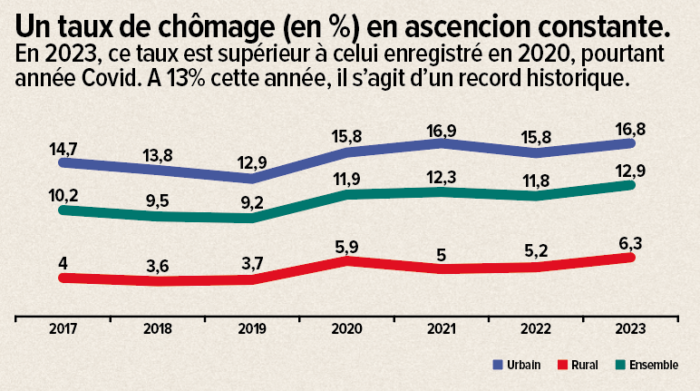

Recent figures from the HCP regarding the labor market in 2023 indeed paint a bleak picture. A 13% unemployment rate (+138,000 unemployed), the worst in our history; a youth unemployment rate for those aged 15 to 24 of 35.8%; a female labor force participation rate of barely 19%…

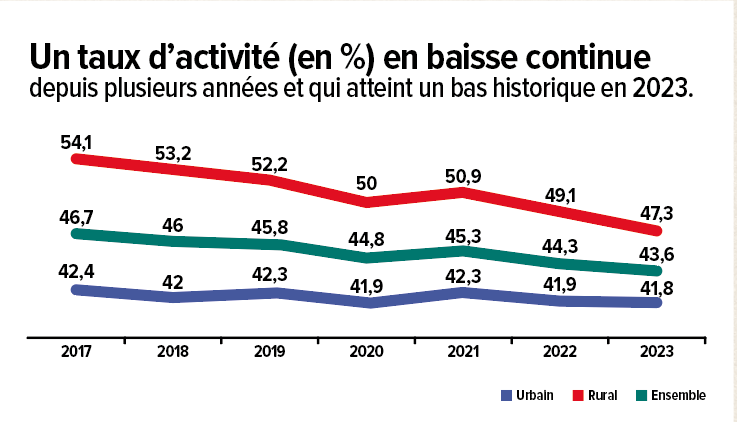

Simply put, all indicators are red. With an employment rate of 38% and a labor force participation rate of 41.8%, Morocco has never been so inactive, so lethargic, and idle. These alarming figures come in a year of positive growth.

Growth that destroys jobs

According to the World Bank, the kingdom’s GDP is expected to grow by 2.8% in 2023 (final figures have not yet been determined). Whereas less than a decade ago, one percentage point of GDP created between 20,000 and 30,000 jobs, today, the same percentage point destroys just over 56,000 jobs.

Certainly, the series of external shocks and years of drought play a role in this chaotic scenario. In this context, most job losses have been observed in rural areas (198,000 positions lost).

Nevertheless, where the government has leverage, namely in urban areas, the results are still below average. Only 41,000 net jobs have been created in cities. This is in a country that sees between 300,000 and 400,000 new job seekers entering the labor market each year.

Despite the kingdom’s industrial ambitions and numerous announcements about factory openings and future investment commitments, the industry has created only 7,000 net jobs. This figure includes crafts. Despite the government’s focus on it, the manufacturing sector accounts for only 12.2% of employment in Morocco, which remains a service-oriented country.

It is also noted, when examining the HCP report, that the construction sector, typically known for creating between 50,000 and 100,000 jobs annually in a country that resembles an open-air construction site, has generated only 19,000 net jobs. This decline is attributed to the three successive increases in the key interest rate decided by the governor of Bank Al-Maghrib.

By increasing the cost of credit, Abdellatif Jouahri has postponed many of the construction projects scheduled for 2023, resulting in the low job creation in the sector.

Another point to note is the struggling health of businesses, particularly cafes, restaurants, and hammams. These job providers, burdened by numerous taxes and regulations, are dwindling.

The non-outsourcable retail sector, a cornerstone of employment that, while low-paying, is abundant, lost 74,000 jobs in 2023. It’s a real Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre.

It should be noted that “the new jobs created in this sector (services, editor’s note) mainly come from the creation of 31,000 positions in ‘social services provided to communities’ (education, health, social action, etc.),” according to the HCP note.

Overall, between the jobs lost in retail and those created in other areas, services generated 15,000 net jobs. It’s modest but enough to make it the primary engine of employment in the country.

Regionalization not very advanced

What is most disconcerting is that despite the advanced regionalization project and the encouragement of decentralization, national employment remains highly concentrated. For instance, only 5 regions account for 72.6% of the working-age population. A region like Souss-Massa, which is the stronghold of Aziz Akhannouch, who is also the mayor of Agadir, has the lowest activity rate in Morocco: a mere 39%. As for the Southern provinces, the unemployment rate there is the highest in the kingdom: 20.3%.

With 300 billion dirhams in public investment in 2023—a record—many observers expected more promising results. But are state resources being directed towards projects that truly generate jobs?

In short, growth that does not create jobs, is poorly distributed spatially, and an economic machine that is clearly malfunctioning. Yet, through public procurement, the state spares no effort to stimulate the economy. With 300 billion dirhams in public investment in 2023—a record—many observers expected more promising results. However, the quality of this investment is questionable. Are state resources being directed towards projects that truly generate jobs?

The World Bank has frequently noted that Morocco, one of the countries with the highest public investment relative to its GDP (30%), has one of the lowest ICORs (Incremental Capital-Output Ratios) among countries in its category. In other words, while money flows into numerous projects, these projects yield insignificant returns on investment, with very little impact on both growth and employment.

Moreover, the state is not supported by the private sector. In launching the famous investment charter, King Mohammed VI aimed to encourage the private sector to invest 550 billion dirhams by 2026.

Where has the private sector gone?

However, the private sector stands out for its timidity. The Minister Delegate to the Head of Government in charge of investment, Mohcine Jazouli, recently boasted (without providing detailed figures) that the private sector invested 100 billion dirhams in the economy in 2022.

This figure might seem impressive, but it is, in fact, quite ordinary. It simply reflects the traditional distribution of national investment, with one-third coming from the private sector and the remaining two-thirds covered by public authorities.

However, the king specifically wants to reverse this trend. At the current rate, the goal seems somewhat compromised. The Head of Government himself, in a speech to the second chamber at the end of December 2023, expressed concern about the anemia of private investments.

In response to the criticisms from the head of the CGEM regarding the lack of dynamism from the state, Akhannouch indirectly reproached the major business leaders for not contributing financially despite the government’s generous support towards them (such as VAT refunds, reductions in corporate tax, cuts in dividend tax rates, subsidies for the tourism sector and transporters, etc.).

Unemployment rates figures

The temptation of dissent

Akhannouch and his team have yet to find the PIN code capable of revitalizing the Moroccan economy. Naturally, justifications will be forthcoming, and the Ministers of Employment and Industry will make their usual efforts to question the HCP figures.

The Minister of Industry, Ryad Mezzour, who is also very active in promoting « Made in Morocco » (which should be acknowledged), had reported the creation of 100,000 jobs in the industry in 2023.

While Ahmed Lahlimi’s services, the head of the HCP, reported a loss of 297,000 jobs in October 2023, the Minister of Labor, through a cryptic and incomprehensible calculation, claimed that the economy had not only not destroyed a single job but had created 621,000 wage jobs (sic).

Similarly, Minister of Industry Ryad Mezzour, who is also very active in promoting « Made in Morocco » (which should be acknowledged), had reported the creation of 100,000 jobs in the industry in 2023. However, the reality is different: only 7,000 net jobs were generated in the industry, a figure that includes the crafts sector.

Declining activity rate figures

“The worst thing that could happen is that instead of acknowledging these catastrophic figures, the government starts to contest them. This would mean that we are not learning from our mistakes.“

« The worst thing that could happen is that instead of acknowledging these catastrophic figures, the government starts to contest them. This would mean that we are not learning from our mistakes; given the extent of the catastrophe, it is essential to analyze these figures with a clear mind and radically change economic strategy, » advises this economist.

Certainly, the government is trying to revive the entrepreneurial spirit among young people with initiatives like Forsa. However, with barely 10,000 projects financed annually, the yield is poor. Even the Awrach program, which aims to create temporary positions on public construction sites, does not appear on the HCP’s radar.

Yet, the Minister of Employment, Younes Sekkouri, had announced the anticipated creation of 150,000 Awrach positions in 2023. “A precise audit of these figures is necessary, as these 150,000 announced positions alone could have brought us closer to a positive overall job creation scenario,” notes a statistician.

In this maze of figures coming from the government, it is indeed difficult to see clearly. However, argues our economist, “the baseline is the HCP; everything else is just a publicity stunt and an attempt to cover up a fundamentally poor record.”

Radically change the approach

Just as the government is currently demonstrating energy in finding solutions to the water scarcity issue, it will need to apply the same vigor to radically revising our economic model. In particular, this historical link between rainfall and job activation that no government has managed to break must be addressed.

The proverbial demographic dividend that Morocco once enjoyed has already been squandered. Young people are increasingly struggling to enter the labor market. Those with a diploma face an unemployment rate (19.7%) significantly higher than those who have never attended school (4.9%).

This is an equation that the government must adjust, or it risks destabilizing the country in the coming years. With a private sector lacking confidence, a state that invests but with very low returns on investment, and unfortunately, a drastic decline in net FDI compared to 2022 (-53%), where will salvation come from? This is the question that Aziz Akhannouch and his teams must answer.

Yet, the situation has not always been so catastrophic. The Jettou, El Fassi, Benkirane, and El Othmani governments were net creators of jobs, despite numerous external shocks, including the famous subprime crisis in 2008. In the last pre-Covid year, 2019, the economy had generated 119,000 net jobs under El Othmani. However, Akhannouch is struggling to achieve this, despite the Morocco momentum, a global aura that the kingdom should leverage to energize its economy and revive its job creation machine.

Tick-tock…

Clearly, despite the kingdom’s intrinsic advantages, this government has not found the magic formula. For the good of the country, one can only hope that it awakens from its inertia, changes its approach, and implements the necessary reforms to provide Moroccans with an economy that matches their aspirations for emergence.

Perhaps it could start by applying the recommendations of the New Development Model, a comprehensive and detailed roadmap guiding us towards emergence by 2035. Yet, this essential document, the result of forward-looking reflection initiated by King Mohammed VI, has strangely been kept under wraps.

In the end, Aziz Akhannouch faces one of the most extreme stress tests: reviving growth and employment as quickly as possible, or risk condemning his mandate to failure along with the country. Often, the Head of Government boasts about preferring action to words. For him, the time to act has arrived. But beware, time is running out…

Written in French by Réda Dalil, edited in English by Eric Nielson