Without a better understanding of business dynamics in Morocco, designing public policies to accelerate economic growth and job creation is impossible. With this in mind, the World Bank and the Moroccan Observatory for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (OMTPME)—an institution established by the Central Bank and its partners—collaborated to analyze the dynamics and productivity of businesses in Morocco.

To achieve this, the two institutions compiled and processed a comprehensive dataset sourced from key public administrative entities. These sources include the General Tax Directorate (DGI), the National Social Security Fund (CNSS), Bank Al-Maghrib (BAM), the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Moroccan Office of Industrial and Commercial Property (OMPIC), and the National Agency for the Promotion of Small and Medium Enterprises (Maroc PME). The OMTPME dataset encompasses a panel of approximately 370,000 registered businesses, with data spanning from 2012 to 2022.

Small businesses dominate

The first key insight from the report, presented on October 15 in Rabat, reveals that Morocco’s formal productive sector is overwhelmingly dominated by small businesses. In 2021, Morocco had 370,000 formal enterprises. Microenterprises, with annual revenues of up to 1 million dirhams, accounted for 78.8% of all businesses. They were followed by 9.2% of businesses with revenues between 1 and 3 million dirhams.

Medium-sized enterprises, with annual revenues ranging from 50 million to 175 million dirhams, made up just 0.9%, while large enterprises, generating more than 175 million dirhams in revenue, represented only 0.4% of all businesses, as shown below.

Similar patterns emerge when businesses are evaluated based on employment size. The majority of companies (81.6%) employ fewer than 10 people, while only 4.9% have more than 50 employees, as illustrated in the accompanying chart.

Additionally, formal businesses tend to be concentrated both sectorally and geographically. Half of the companies in the OMTPME database are in the retail trade and construction sectors. Geographically, three major urban areas account for over 50% of all businesses: Casablanca-Settat (35.5%), Rabat-Kenitra (14%), and Tangier-Tetouan (11%).

Rising density, but…

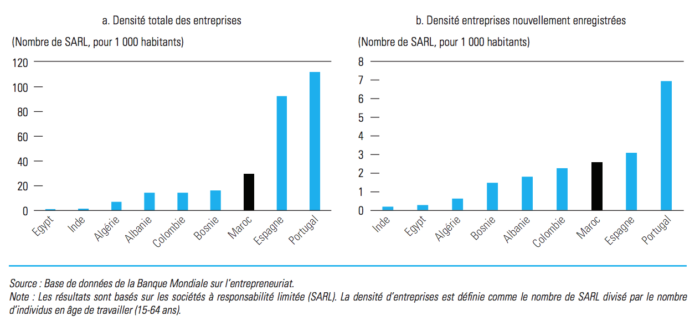

“The analysis of business density in Morocco, measured by the number of legal entities per 1,000 inhabitants, reveals a notable increase driven primarily by a surge in new businesses entering the market,” said Amal Idrissi, Executive Director of OMTPME, during the report’s presentation. The density of formal businesses relative to Morocco’s population has indeed risen significantly and compares favorably with most peer countries.

Since 2006, the net number of Limited Liability Companies (SARLs) has grown steadily, leading to a quadrupling of business density during this period. With 29.7 SARLs per 1,000 inhabitants, Morocco’s business density surpasses that of most comparable countries. However, this indicator remains four to five times higher in advanced economies such as Spain and Portugal.

In terms of new business density, Morocco also outpaces most of its peers, with the exception of Spain and Portugal. According to the report, the growth in formal business density has been supported by the rapid expansion of new business creation. The number of private-sector companies operating formally in Morocco increased from 245,000 in 2017 to 317,000 in 2021, representing a 30% growth.

This trend is largely attributable to the increase in new business openings, which rose from 79,000 in 2017 to 105,000 in 2021. “This partly reflects the efforts of Moroccan authorities to improve the business climate, as well as the regulatory and institutional framework promoting business formalization,” explains Amal Idrissi. “It is therefore a positive indicator of the public policies implemented in Morocco. That said, the rise in business density in Morocco should be interpreted with caution, as we will see with the business exit rate.”

Difficult exit

According to the report, the recent increase in business density is largely explained by a notably low administrative de jure exit rate, as many businesses become inactive without officially closing. In 2019, only 1.2% of registered businesses had formally ceased operations, even though 7.9% of formal legal entities in 2018 ceased activity in 2019 without officially closing. In reality, nearly 80% of these businesses remained inactive in 2020. “When accounting for these effective closures, the de facto exit rate—meaning the proportion of businesses that are inactive for at least two consecutive years—was 7.3%,” the document notes.

This significant gap between de jure and de facto exit rates in Morocco “suggests that a large part of the observed increase in business density in the country is due to a rise in business inactivity rates rather than an increase in the density of businesses actually active in the economy.”

Behind this issue lies the difficulty for nonviable Moroccan businesses to close. Despite significant legal progress, Morocco still lacks a streamlined process to minimize the costs associated with business exits, and some regulations seem to allow inefficient businesses to remain in the market. “To foster a diverse entrepreneurial environment, it is essential to facilitate not only business entry but also business exit. The exit of nonviable businesses is critical to prevent resources from being unnecessarily tied up, complicating debt recovery and stifling economic dynamism,” explains Amal Idrissi.

“In conclusion, these observations suggest that while starting a business is administratively easy, bankruptcy and liquidation procedures remain inefficient and costly. The business exit rate after five years of existence is only 53%,” adds the OMTPME director.

Stagnating businesses

To better understand this « reality already highlighted by international reports and observatories, » the authors of the report also analyzed the growth dynamics of Moroccan businesses. It reveals that the average size of Moroccan businesses has “at best stagnated in recent years.” The average turnover of very small enterprises (TPEs) decreased from 1.6 million MAD in 2017 to 1.4 million MAD in 2020, while the turnover of medium and large enterprises only increased modestly (from 361 million MAD in 2017 to 368 million MAD in 2021). The number of jobs has also declined, dropping from 12 to 11 employees for TPEs and from 371 to 343 employees for medium and large enterprises.

This stagnation in the size of Moroccan businesses is observed across all age groups. A Moroccan business active for 15 years employs, on average, 187% more workers than a one-year-old business with similar activity. This age-size relationship is very similar to that observed in Vietnam, “one of Morocco’s aspirational peer countries.” However, this relationship is largely driven by the de facto exit of smaller businesses, which cease operations at a higher rate than their larger counterparts. Once this factor is accounted for, the growth over the lifecycle of an average Moroccan business remains limited.

“This contrasts with the situation in Vietnam, where the average size of businesses surviving to the age of 15 is estimated to be 65% larger than their average size at one year of age. This reflects a more dynamic private sector,” explains Amal Idrissi. “This finding underscores the weak growth of Moroccan businesses compared to other countries,” she adds. “This is concerning, as it significantly reduces the potential for job creation, which is a critical issue for Morocco.”

Low productivity of HGFs

The share of High-Growth Firms (HGFs) in Morocco’s formal private sector, typically more innovative, is relatively high. These are companies that, at the start of the study period, had at least 10 employees and, three years later, increased their workforce by at least 20%. However, their density remains very low, with only one HGF per 1,000 inhabitants.

“This low density likely contributes to the slow pace of job creation. A dynamic segment of HGFs generally indicates strong innovation and job creation in the private sector,” as seen in countries like Brazil and Turkey, noted Idrissi. “Still, Morocco performs better than Colombia,” she added.

The report also compares the size, productivity, and age of Morocco’s High-Growth Firms (HGFs). Once again, the findings “are particularly revealing,” says Idrissi. “It appears that these HGFs are generally younger and smaller, while global observations show that high-growth firms are often thriving businesses capable of sustaining high growth rates. However, what is surprising is that these HGFs have lower productivity compared to other non-HGFs in Morocco,” notes the director of OMTPME.

According to her, this may indicate “market distortions,” as it is typically expected that the most productive businesses would also exhibit the highest growth rates. Moroccan HGFs are more commonly found in sectors like construction and relatively low-skilled services, while their presence is much smaller in information and communication technologies (ICT) and manufacturing industries. “This suggests that certain constraints, such as the lack of qualified professionals and limited access to financing, prevent Moroccan businesses from reaching their growth potential. Consequently, mature companies with larger market shares are rarely challenged by newcomers,” she laments.

Written in French by Ghita Ismaili, edited in English by Eric Nielson