One in five Moroccans is obese. One third is overweight. According to current trends, the pandemic of this century might not be bacterial or viral, but rather fat-related. In 1999, a study by the firm Léger et Léger revealed that 11.3% of the Moroccan population was affected by obesity. This proportion, which has doubled in 25 years, could reach 46% by 2035 according to estimates from the « World Obesity Atlas 2023. »

So what happened? It’s hard to believe that Moroccan body size has changed so rapidly. It’s actually the lifestyle habits of Moroccans that have been disrupted, especially their diet, which now contains increasingly more sugar.

Certainly, the Kingdom has always had a sweet tooth. However, today, sugar is no longer just used to sweeten our tea or sprinkle on our desserts. From cereals and bread to processed meats, canned vegetables, sauces, and even chips, sugar is now hidden everywhere. Cheap and calorie-rich, this ingredient has become a staple in all processed food recipes in the agro-food industry.

The impact on sugar consumption is striking. While WHO recommendations suggest an optimal intake of less than 25 g per day (6 teaspoons), or 9 kg per year, the average consumption among Moroccans is 36 kg per year. In 1967, according to the book L’industrie du sucre au Maroc by Jacqueline Bouquerel, they consumed “only” 25 kg per year, marking a 44% increase.

Behind this addictive commodity lie financial interests, subsidies, taxes, lobbying… and an exorbitant cost to the Moroccan economy.

Expensive Sugar

A public health issue, but also a matter of big money. Each year, the Moroccan government supports the sugar market with billions of dirhams. According to the compensation report published by the Ministry of Economy and Finance on the occasion of the 2024 Finance Bill vote, the public treasury will spend no less than 4 billion dirhams to lower the price of sugar on the domestic market.

For Mostafa Brahimi, a deputy and physician, and vice-president of the Social Sectors Committee in the House of Representatives, this subsidy is not inherently bad. He believes it is fair for the state to ensure the accessibility of “essential food products” like sugar for Moroccan households. However, he emphasizes that “the philosophy of compensation is to enable the poorest people to buy sugar at an affordable price.” Brahimi, from the Justice and Development Party (PJD), argues that allowing industries— as is currently the case—to benefit from this subsidy is “not justified,” and that they should pay for the commodity “at market price.”

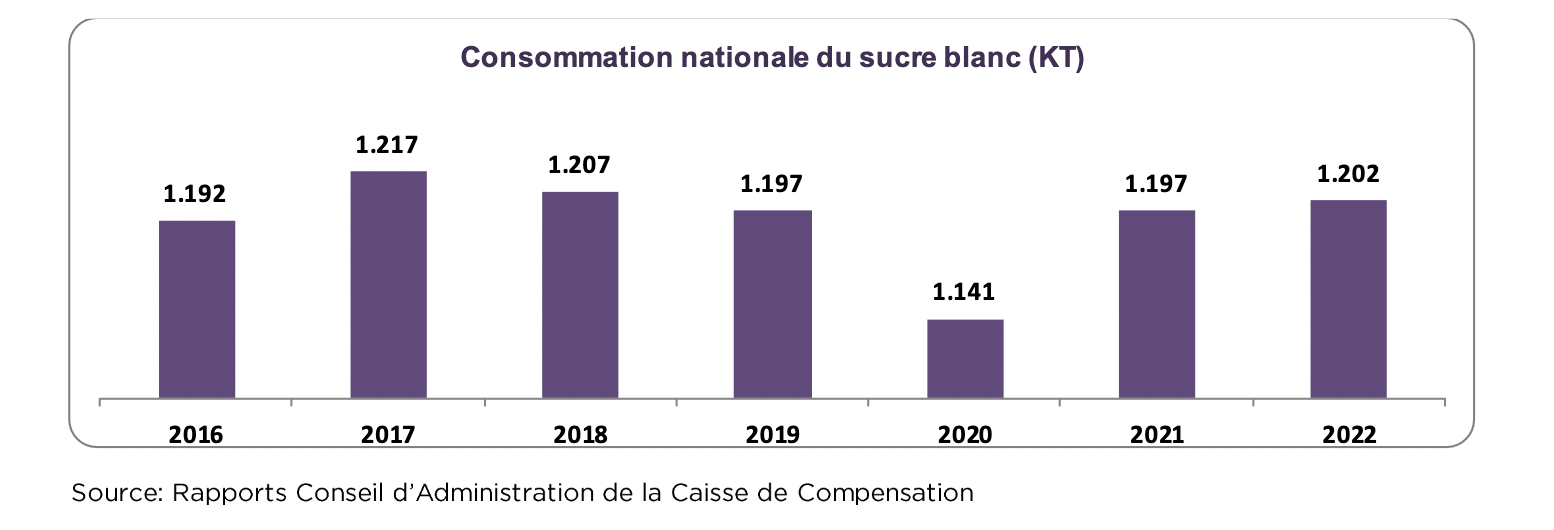

But how much are Moroccan taxpayers subsidizing the industry to feed them sugar in return? According to the Budget Minister, Fouzi Lekjaa, annual sugar consumption in the Kingdom is around 1.2 million tonnes, and 25% of this white mountain is destined for the agro-food industries.

This data is confirmed by the board of directors of the Compensation Fund. In 2023, the fixed subsidy, which increased from 2,847 to 3,571 dirhams per tonne on April 14, is expected to exceed 4 billion dirhams, according to the aforementioned compensation report. 25% of this subsidy amounts to 1 billion dirhams, directly from the public treasury to the industry.

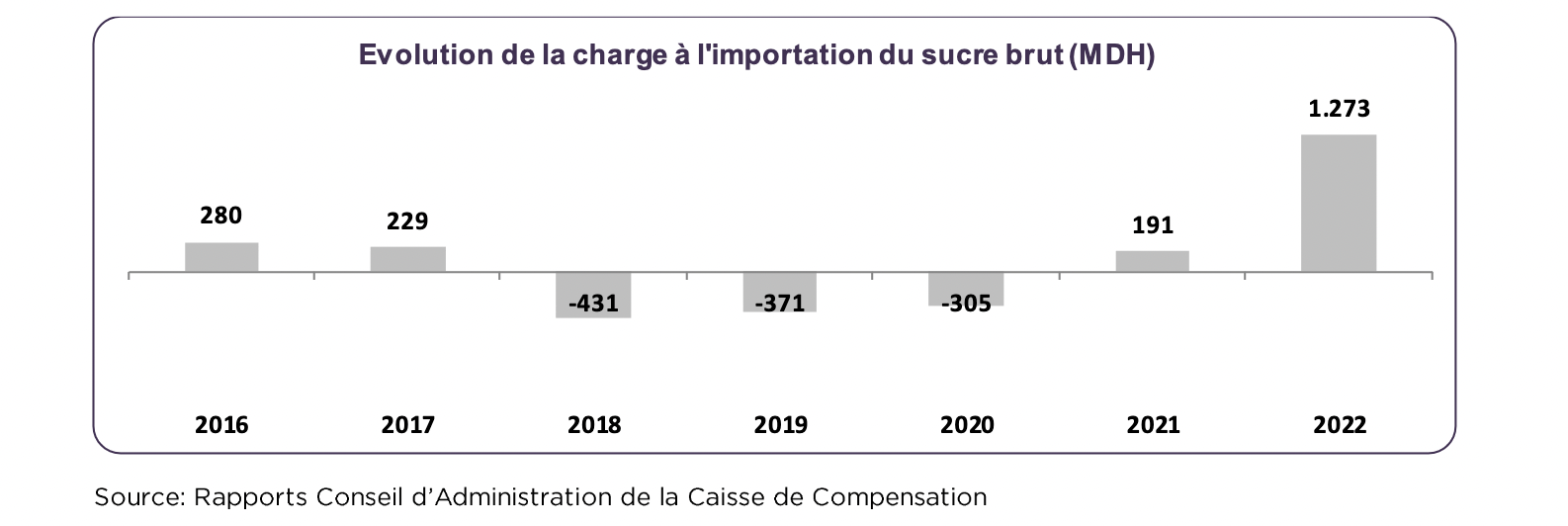

And the trend is not decreasing. In 2022, the same calculation set the subsidy allocated to industries at 850 million dirhams. This year, the amount is expected to rise further. According to the compensation report from the Ministry of Economy, this increase is due to “the staggering rise in global raw sugar prices and the significant increase in imported quantities to cover the growing deficit in domestic production due to the lack of water resources.”

Imported sugar, which made up 55% to 81% of the Moroccan market between 2017 and 2022, benefits from a subsidy influenced by global sugar prices. Thus, in the first half of 2023, the public treasury supported each tonne of imported sugar with 1,987 dirhams, compared to 1,451 in 2022, representing a 37% increase, according to the report. Therefore, it is expected that industries will increasingly benefit from this subsidy intended for Moroccan households.

Why not remove these subsidies? « It’s actually very simple, » says Mostafa Brahimi. He cites the removal of the fuel subsidy on January 1, 2015, or more recently, the partial removal of the gas subsidy on May 20. « This can be done through simple regulatory means, » he asserts. The PJD deputy advocates for a proposal to recover the subsidy from the industries that benefit from it. Such a mechanism already exists. « A recovery equivalent to 1,000 dirhams per ton [of sugar] is established for soft drink companies, » as stated on the Ministry of Economy and Finance’s website.

Nevertheless, due to its lobbying power, the agro-food industry has so far managed to block Mostafa Brahimi’s proposal and that of his supporters. « Some market players go to parliamentarians and ministers and argue that, with free trade agreements, removing the subsidy would disadvantage them against international competition that practices dumping (illegal reduction of sale prices below production costs), » says the deputy. Although « no proof » of dumping by foreign agro-food companies has ever been provided, this “classic argument of stirring fear of factory closures and mass layoffs” seems to work with a government heavily criticized for a latent unemployment crisis.

The agro-food industry also argues that a strategy of making overly sugary products more expensive through tougher fiscal policies is ineffective, says Mostafa Brahimi. The deputy counters this. Based on WHO studies and the application of these practices in countries like Mexico, he notes « tangible results. »

However, it seems that some of these arguments have the ear of the Executive. “The government believes that after the Covid crisis, the war in Ukraine, and recent sugar taxes, removing subsidies would weigh too heavily on the agro-food industry,” explains Mostafa Brahimi. Indeed, with some difficulty, Parliament voted in 2018 for a tax on sugary drinks. In 2022, after « a frank and fruitful debate » with representatives from the agro-food industry and the Executive, the “Moroccan Obesity Task Force” (of which Mostafa Brahimi is a member) secured a tax on « processed products high in sugar such as biscuits, chocolates, dairy products, jam…, » says the deputy. « Morocco received an award from the WHO for the soda tax, » he adds.

According to the 2024 Finance Bill, the tax is progressive:

24 billion dirhams per year

While for the Moroccan Obesity Task Force, the existence of these taxes on sugar is a victory in itself, it is worth noting that the projected revenue from the 2024 Finance Bill on sugar (including both drinks and solids) amounts to 696.3 million dirhams. This is less than the billion dirhams in subsidies that the public treasury paid to industrialists in 2023.

If we attempt to make comparisons, the taxes on sugar will bring in 18 times less than those imposed on tobacco. According to a study by the Ministry of Health, in 2019, the annual economic cost of tobacco in Morocco was 5.2 billion dirhams, or 8.5% of total health expenditures and 0.45% of GDP. Sugar is a much bigger issue. At least, obesity is. While modified carbohydrates—such as sugar in processed foods—are not the sole cause of overweight, they are among the primary contributors.

According to Professor Jaâfar Heikel, a colleague of Mostafa Brahimi in the Moroccan Obesity Task Force, obesity costs the Moroccan economy no less than « 24 billion dirhams per year. » Like tobacco, this figure includes direct medical expenses, indirect costs, and the economic loss of patient productivity. The doctor, president of the Moroccan Society of Nutrition, Health, and Environment, specifies that this represents 70% of the health budget and 3% of GDP.

“We do not want to overtax businesses, but to impose higher taxes on products overloaded with sugar.”

From a public health perspective, Jaâfar Heikel is troubled by “subsidizing sugar present in soft drinks and foods that do not offer nutritional value,” but he is “not against the agro-food industry.” The professor emphasizes his awareness of the importance of having an efficient manufacturing sector in Morocco. “However, I would like there to be a fair balance between economic gain and the health of citizens,” he asserts. He also points out that “when citizens’ health is poor, it impacts the country’s economy.”

Jaâfar Heikel regrets that the Moroccan Obesity Task Force’s project has been perceived as an attack on the agro-food industry. “We do not want to overtax businesses, but to impose higher taxes on products overloaded with sugar,” he explains. The goal of taxing sugar and removing related subsidies is to encourage producers of processed foods to replace sugar in their recipes.

“Sugar is addictive and harmful if consumed in large quantities; countless studies prove this,” he reminds us, highlighting that while it’s not harmful to consume sweet foods, “it should certainly not become the basis of our diet.”

Written in French by Marin Daniel Thézar, edited in English by Eric Nielson